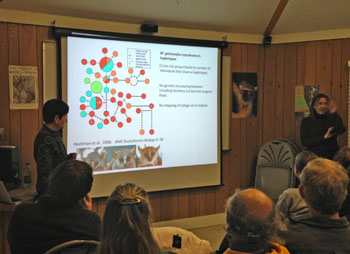

Final presentations for the Neuroscience and Neuroethics Camp were held in the new headquarters of the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences. (photo by Jon Lepofsky)

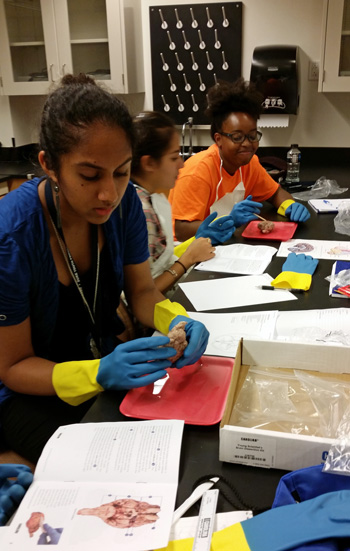

Given just two weeks to formulate a hypothesis about brains, Duke’s Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroethics Camp students spoke with impressive confidence as they presented at the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences (DIBS) on July 16.

The high school students had designed experiments using the concepts and methods of cognitive neuroscience to demonstrate what is unique about human brains.

“It was good to see the curiosity, energy, and critical thinking that was present throughout the students’ projects,” said Jon Lepofsky, Academic Director for the Cognitive Neuroscience & Neuroethics camp, the Duke Youth Programs summer program of hands-on, applied problem-solving activities and labs was developed in partnership with DIBS.

Lepofsky said he was pleased to start the first year of the camp with an engaged, diverse, and thoughtful group of 22 students.

Andie Meddaugh, Xi Yu Liu, Emily Lu and Anand Wong were working on a project involving the logic and the emotion of the human brain. Their hypothesis was that the ability to combine logic and emotion to create a subjective logic shows the difference between human brains and other intelligence processing systems, like artificial intelligence.

Meddaugh said she liked thinking about the brain and logic.

“I enjoy thinking about the problem of what makes us special,” said Meddaugh.

Another group of students presented a project involving the social construct and morality of the brain.

Nicolas Douglass, Abigail Efird, Grace Garret and Danielle Dy are using a hypothesis that suggests if organisms are presented with an issue of resource availability how they respond is a matter of survival. They proposed using birds, humans, and monkeys to test the reactions of each organism as it is placed outside of its comfort zone.

Abigail Efird said teamwork and “aha moments” were the best way to conduct this project.

“It took human ingenuity and scientific development in order for us to come up with different strategies,” said Efird. “It was surprising to see that humans are not as special and are very much similar to other organisms. “

Lepofsky said at the end of the program, students will leave with a new set of critical thinking tools and a better understanding of decision- making.

“I know the students will walk away with a deeper understanding of how to evaluate news stories celebrating neuroscience,” Lepofsky said. “They will know how to think like scientists and how to ask quality questions.”

Along with developing a hypothesis on the human brain, the students participated in interactive workshops on perception and other forms of non-conscious processing with Duke researchers. They’ve engaged in debates about topics in neuroethics and neurolaw. In addition to that they went on lab tours and visits to the DiVE.

For more information on Duke’s Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroethics Camp visit http://www.learnmore.duke.edu/youth/neurosciences/ or call (919) 684-6259.