Duke launches free two-week girls science camp in Pisgah National Forest.

DURHAM, N.C. — To listen to Destoni Carter from Raleigh’s Garner High School, you’d never know she had a phobia of snails. At least until her first backpacking trip, when a friend convinced her to let one glide over her outstretched palm.

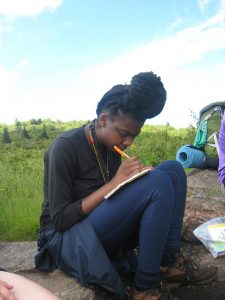

Destoni Carter from Raleigh’s Garner High School was among eight high schoolers in a new two-week camp that combines science and backpacking.

Soon she started picking them up along the trail. She would collect a couple of snails, put them on a bed of rocks or soil or leaves, and watch to see whether they were speedier on one surface versus another, or at night versus the day.

The experiment was part of a not-so-typical science class.

From June 11-23, 2017, eight high school girls from across North Carolina and four Duke Ph.D. students left hot showers and clean sheets behind, strapped on their boots and packs, and ventured into Pisgah National Forest.

For the high schoolers, it was their first overnight hike. They experienced a lot of things you might expect on such a trip: Hefty packs. Sore muscles. Greasy hair. Crusty socks. But they also did research.

The girls, ages 15-17, were part of a new free summer science program, called Girls on outdoor Adventure for Leadership and Science, or GALS. Over the course of 13 days, they learned ecology, earth science and chemistry while backpacking with Duke scientists.

Duke ecology Ph.D. student Jacqueline Gerson came up with the idea for the program. “Backpacking is a great way to get people out of their comfort zones, and work on leadership development and teambuilding,” said Gerson, who also teamed up with co-instructors Emily Ury, Alice Carter and Emily Levy, all Ph.D. students in ecology or biology at Duke.

Marwa Hassan of Riverside High School in Durham studying stream ecology as part of a two-week summer science program in Pisgah National Forest. Photo by Savannah Midgette.

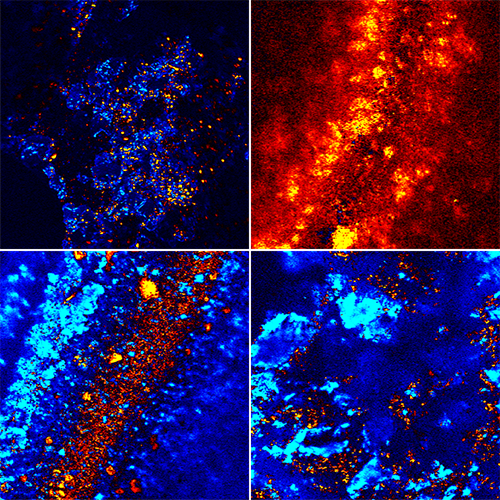

The students hauled 30- to 40-pound loads on their backs for up to five miles a day, through all types of weather. For the first week and a half they covered different themes each day: evolution, geology, soil formation, aquatic chemistry, contaminants. Then on the final leg they chose an independent project. Armed with hand lenses, water chemistry test strips, measuring tapes and other gear, each girl came up with a research question, and had two days to collect and analyze the data.

Briyete Garcia-Diaz of Kings Mountain High School surveyed rhododendrons and other trees at different distances from streambanks to see which species prefer wet soils.

Marwa Hassan of Riverside High School in Durham waded into creeks to net mayfly nymphs and caddisfly larvae to diagnose the health of the watershed.

Savannah Midgette of Manteo High School counted mosses and lichens on the sides of trees, but she also learned something about the secret of slug slime.

“If you lick a slug it makes your tongue go numb. It’s because of the protective coating they have,” Midgette said.

High schoolers head to the backcountry to learn the secret of slug slime and other discoveries of science and self in new girls camp

The hiking wasn’t always easy. On their second day they were still hours from camp when a thunderstorm rolled in. “We were still sore from the previous day. It started pouring. We were soaking wet and freezing. We did workouts to keep warm,” Midgette said.

At camp they took turns cooking. They stir fried chicken and vegetables and cooked pasta for dinner, and somebody even baked brownies for breakfast. Samantha Cardenas of Charlotte Country Day School discovered that meals that seem so-so at home taste heavenly in the backcountry.

“She would be like, ugh, chicken in a can? And then eat it and say: ‘That’s the most amazing thing I’ve ever had,’” said co-instructor Emily Ury.

Savannah Midgette and Briyete Garcia-Diaz drawing interactions within terrestrial systems as part of a new free summer science program called Girls on outdoor Adventure for Leadership and Science, or GALS. Learn more at https://sites.duke.edu/gals/.

The students were chosen from a pool of over 90 applicants, said co-instructor Emily Levy. There was no fee to participate in the program. Thanks to donations from Duke Outdoor Adventures, Project WILD and others, the girls were able to borrow all the necessary camping gear, including raincoats, rain pants, backpacks, tents, sleeping bags, sleeping pads and stoves.

The students presented their projects on Friday, June 23 in Environment Hall on Duke’s West Campus. Standing in front of her poster in a crisp summer dress, Destoni Carter said going up and down steep hills was hard on her knees. But she’s proud to have made it to the summit of Shining Rock Mountain to see the stunning vistas from the white quartz outcrop near the top.

“I even have a little bit of calf muscle now,” Carter said.

Funding and support for GALS was provided by Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke ecologist Nicolette Cagle, the Duke Graduate School and private donors via GoFundMe.

2017 GALS participants (left to right): Emily Levy of Duke, Destoni Carter of Garner High School, Zyrehia Polk of East Mecklenburg High School, Rose DeConto of Durham School of the Arts, Briyete Garcia-Diaz of Kings Mountain High School, Marwa Hassan of Riverside High School, Jackie Gerson of Duke, Daiana Mendoza of Harnett Central High School, Savannah Midgette of Manteo High School, Samantha Cardenas of Charlotte Country Day School and Alice Carter of Duke.

Post by Kara Manke

Post by Kara Manke