The first decentralized cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, was created in 2009 by a developer named Satoshi Nakamoto which is assumed to be a pseudonym. Over the last decade, cryptocurrency has taken the world by storm, influencing the way people think about the intersection of society and economics. Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin or Ethereum, another popular token, operate on blockchains.

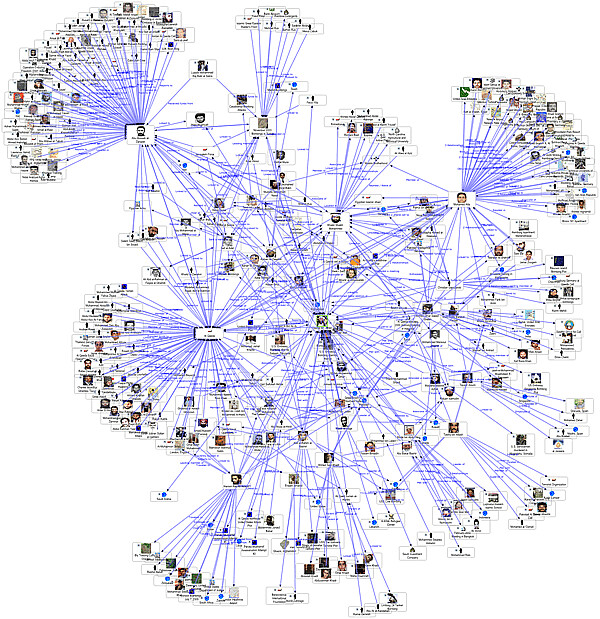

Manmit Singh, a senior studying electrical and computer engineering, was introduced to blockchain his freshman year at Duke after meeting Joey Santoro ‘19, a senior studying computer science at the time.

Singh quickly found that he was not only interested in the promise of blockchain but skilled at building blockchain applications as well. As a result, he joined the Duke blockchain lab, a club on campus that, at the time, had no more than fifteen students. Singh, who is now president of the Duke Blockchain Lab, explained that there are now over 100 members in the club working on different projects related to blockchain.

“Blockchain is a computer network with a built-in immutable ledge.”

Manmit SIngh

Essentially, computers process information, the internet allows us to communicate information and blockchain is the next step in the evolution of the digital era. It not only allows computers to communicate value but to transfer it as well in a completely transparent way because every transaction is tracked and, a record of that transaction is added to every participant’s ledger which is visible to others.

The concept and application of blockchain is not intuitive to everybody. Not only do people have difficulty understanding it, but they do not even know where to begin asking questions.

For Singh, a key element to the club’s success was recruiting new members. The crypto space experienced a crash in 2017 resulting in a lot of skepticism around an already novel idea, decentralized currency. As a result, it was crucial to educate others on the potential of decentralized finance (DeFi), cryptocurrency, and, of course, blockchain. When recruiting, Singh wanted to bring in both tech and business-focused students so that they could not only work on building blockchain applications but conduct research on business models and how to generate value within decentralized finance as well.

weekly meeting learning about Stablecoins,

one type of token in cryptocurrency

Currently, members are working on a variety of projects including looking at consensus algorithms or how the blockchain makes decisions given that it is decentralized so inherently no one is in control. However, their most ambitious venture is the development of their Crypto Fund where people can invest money.

They are also looking to develop a Duke-inspired marketplace with talented Duke artists to sell non-fungible-tokens or NFTs. If unfamiliar, Abby Shlesinger, a senior studying Art History, created a blog to educate people on what NFTs are.

One of the first projects Singh led involved developing a “smart contract” for cryptocurrency-based energy trading on the Ethereum Virtual Machine, a computation engine that acts like a decentralized computer that can hold millions of executable projects. Smart contracts are programs stored on a blockchain that run when predetermined conditions are met.

Additionally, Singh and other members of the Duke Blockchain Lab are working on tokenomic research with Dr. Harvey, a Duke professor who recently published a book alongside Santoro titled “DeFi and the Future of Finance” which you can find here.

“Every blockchain is a complete economy that exists on a different plane.”

Within these blockchain economies are various different types of tokens that vary in function and value. Tokenomics explores how these economies work and can be used to generate value. When asked to compare tokenomic concepts to ones in traditional finance, Singh explained that payment tokens are like dollars, asset tokens are like bonds and security tokens are like stocks. Currently, several companies are working on creating competitive blockchains that will be both cheaper and faster allowing creating an avenue for blockchain to continue accelerating into the mainstream.

Meanwhile, Santoro, who introduced Singh to blockchain, graduated from Duke in 2019 and went on to form The Fei Protocol, a stable coin that unlike bitcoin does not change in value. His protocol raised one billion dollars within several weeks and while it had some initial challenges, it is now set to launch V2, a second version, soon.

Singh plans to continue working on blockchain applications after graduating this spring and hopes to combine it with his passion for entrepreneurship.

“I am enthused by the applications of artificial intelligence, blockchain, and the internet of things in disrupting the world as we know it.”

Manmit Singh

Written by Skylar Hughes, Class of 2025

Written by Skylar Hughes, Class of 2025