A handful of bird species survived the K-T extinction. Chicken genomes have changed the least since that terrible day.

By Karl Leif Bates

In the beginning was the Chicken. Or something quite like it.

At that moment 66 million years ago when an asteroid impact caused the devastating Cretaceous–Tertiary (K-T) extinction, a handful of bird-like dinosaur species somehow managed to survive.

The cataclysm and its ensuing climate change wiped out much of Earth’s life and brought the dinosaurs’ 160-million-year reign to an end.

But this week, the genomes of modern birds are telling us that a few resourceful survivors somehow scratched out a living, reproduced (of course), and put forth heirs that evolved to adapt into all the ecological niches left vacant by the mass extinction. From that close call, birds blossomed into the more than 10,000 spectacularly diverse species we know today.

Not all birds are descended from chickens, but it’s true that chicken genes have diverged the least from the dinosaur ancestors, says Erich Jarvis, an associate professor of neurobiology in the Duke Medical School and Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

He’s one of the leaders on a gigantic release of scientific data and papers that tells the story of the plucky K-T survivors and their descendants, redrawing many parts of the bird family tree.

From giant, flightless ostriches to tiny, miraculous hummingbirds, the descendants of those proto-birds now rule over the skies, the forests, the cliff-faces and prairies and even under water. While other birds were learning to reproduce songs and sounds, hover to drink nectar, dive on prey at 230 miles per hour, run across the land at 40 miles per hour, migrate from pole to pole or spend months at sea out of sight of land, the chickens just abided, apparently.

Sweet little chickadees had a very big, very scary cousin. “Parrots and songbirds and hawks and eagles had a common ancestor that was an apex predator,” Erich Jarvis says. “We think it was related to these giant ‘terror birds’ that lived in the South American continent millions of years ago.”

The new analyses released this week are based on complete-genome sequencing done mostly at BGI (formerly Beijing Genomics Institute). and DNA samples prepared mostly at Duke. The budgerigar, a parrot, was sequenced at Duke. There are 29 papers in this first release, but many more will tumble out for years to come.

“In the past, people have been using 1, 2, up to 20 genes, to try to infer species relationships over the last 100 million years or so,” Jarvis says. But whole-genome analysis drew a somewhat different tree and yielded important new insights.

More than 200 researchers at 80 institutions dove into this sea of big data like so many cormorants and pelicans, coming up with new insights about how flight developed and was lost several times, how penguins learned to be cold and wet and fly underwater and how color vision and bright plumage co-evolved.

The birds’ genomes were found to be pared down to eliminate repetitive sequences of DNA, but yet to still hold microchromosomal structures that link them to the dinosaurs and crocodiles.

The sequencing of still more birds continues apace as the Jarvis lab at Duke does most of the sample preparation to turn specimens of bird flesh into purified DNA for whole-genome sequencing at BGI. (More after the movie!)

As one of three ring-leaders for this massive effort, Erich Jarvis is on 20 papers in this first set of findings. Eight of those concern the development of song learning and speech, but the other ones are pretty cool too:

Evidence for a single loss of mineralized teeth in the common avian ancestor. Robert W. Meredith, et al. Science. Instead of teeth, modern birds have a horny beak to grab and a muscular gizzard to “chew” their food. This analysis shows birds lost the use of five genes related to making enamel and dentin just once about 116 million years ago.

Complex evolutionary trajectories of sex chromosomes across bird taxa. Qi Zhou, et al. Science. The chromosomes that determine sex in birds, the W and the Z, have a very complex history and more active genes than had been expected. They may hold the secret to why some birds have wildly different male and female forms.

Three crocodilians genomes reveal ancestral patterns of evolution among archosaurs. Richard E Green, et al Science. Three members of the crocodile lineage were sequenced revealing ‘an exceptionally slow rate of genome evolution’ and a reconstruction of a partial genome of the common ancestor to all crocs, birds, and dinosaurs.

Evidence for GC-biased gene conversion as a driver of between-lineage differences in avian base composition. Claudia C. Weber, et al, Genome Biology. The substitution of the DNA basepairs G and C was found to be higher in the genomes of birds with large populations and shorter generations, confirming a theoretical prediction that GC content is affected by life history of a species.

Low frequency of paleoviral infiltration across the avian phylogeny. Jie Cui, et al. Genome Biology. Genomes maintain a partial record of the viruses an organism’s family has encountered through history. The researchers found that birds don’t hold as much of these leftover bits of viral genes as other animals. They conclude birds are either less susceptible to viral infection, or better at purging viral genes.

Genomic signatures of near-extinction and rebirth of the Crested Ibis and other endangered bird species. Shengbin Li, et al Genome Biology. Genomes of several bird species that are recovering from near-extinction show clues to the susceptibilities to climate change, agrochemicals and overhunting that put them in peril. This effort has created better information for improving conservation and breeding these species back to health.

Dynamic evolution of the alpha (α) and beta (β) keratins has accompanied integument diversification and the adaptation of birds into novel lifestyles. Matthew J. Greenwold, et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology. Keratin, the structural protein that makes hair, fingernails and skin in mammals, also makes feathers. Beta-keratin genes have undergone widespread evolution to account for the many forms of feathers and claws among birds.

Comparative genomics reveals molecular features unique to the songbird lineage. Morgan Wirthlin, et al. BMC Genomics. Analysis of 48 complete bird genomes and 4 non-bird genomes identified 10 genes unique to the songbirds, which account for almost half of bird species today. Two of the genes are more active in the vocal learning centers of the songbird brain.

Reconstruction of gross avian genome structure, organization and evolution suggests that the chicken lineage most closely resembles the dinosaur avian ancestor. Michael N. Romanov, et al. BMC Biology. Of 21 bird species analyzed, the chicken lineage appears to have undergone the fewest changes compared to the dinosaur ancestor.

Two Antarctic penguin genomes reveal insights into their evolutionary history and molecular changes related to the cold aquatic environment. Cai Li, et al. Gigascience. The first penguins appeared 60 million years ago during a period of global warming. Comparisons of two Antarctic species show differences and commonalities in gene adaptations for extreme cold and underwater swimming.

Evolutionary genomics and adaptive evolution of the hedgehog gene family (SHH, IHH, and DHH) in vertebrates. Joana Pereira, et al. PLoS ONE. Whole-genome sequences for 45 bird species and 3 non-bird species allow a more detailed tracing of the evolutionary history of three genes important to embryo development.

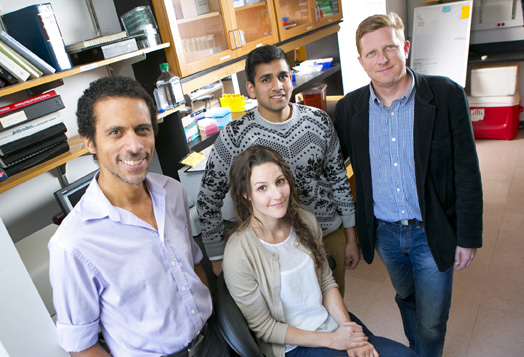

A Duke lab led the effort to isolate bird DNA for sequencing at BGI: (L-R) Erich Jarvis, associate professor of neurobiology and Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, lab research analyst Carole Parent, undergraduate research assistant Nisarg Dabhi, and research scientist Jason Howard. (Duke Photo, Les Todd)