Imagine a robot small enough to fit on a U.S. penny. Or even small enough to rest on Lincoln’s chest. It sounds preposterous enough. Now, imagine a robot small enough to rest on the chest of Lincoln – not the Lincoln whose head decorates the front side of the penny, but the even tinier version of him on the back.

Before it was changed to a Union Shield, the tail side of pennies contained the Lincoln Memorial, including a miniscule representation of the seated Lincoln statue that rests inside. Barely visible to the naked eye, this miniature Lincoln is on the order of a few hundred micrometers wide. As incredible as it sounds, this is the scale of robots being built by Professor Itai Cohen and his lab at Cornell University. On February 22, Cohen shared several of his lab’s cutting-edge technologies with an audience in Duke’s Schiciano Auditorium.

To begin, Cohen describes the challenge of building robots as consisting of two distinct parts: the brain of the robot, and the brawn. The brain refers to the microchip, and the brawn refers to the “legs,” or actuating limbs of the robot. Between these two, the brain – believe it or not – is the easy part. As Cohen explains, “fifty years of Moore’s Law has solved this problem.” (In 1965, Gordon Moore theorized that roughly every two years, the number of transistors able to fit on microchips will double, suggesting that computational progress will become exponentially more efficient over time.) We now possess the ability to create ridiculously small microcircuits that fit on the footprint of a few micrometers. The brawn, on the other hand, is a major challenge.

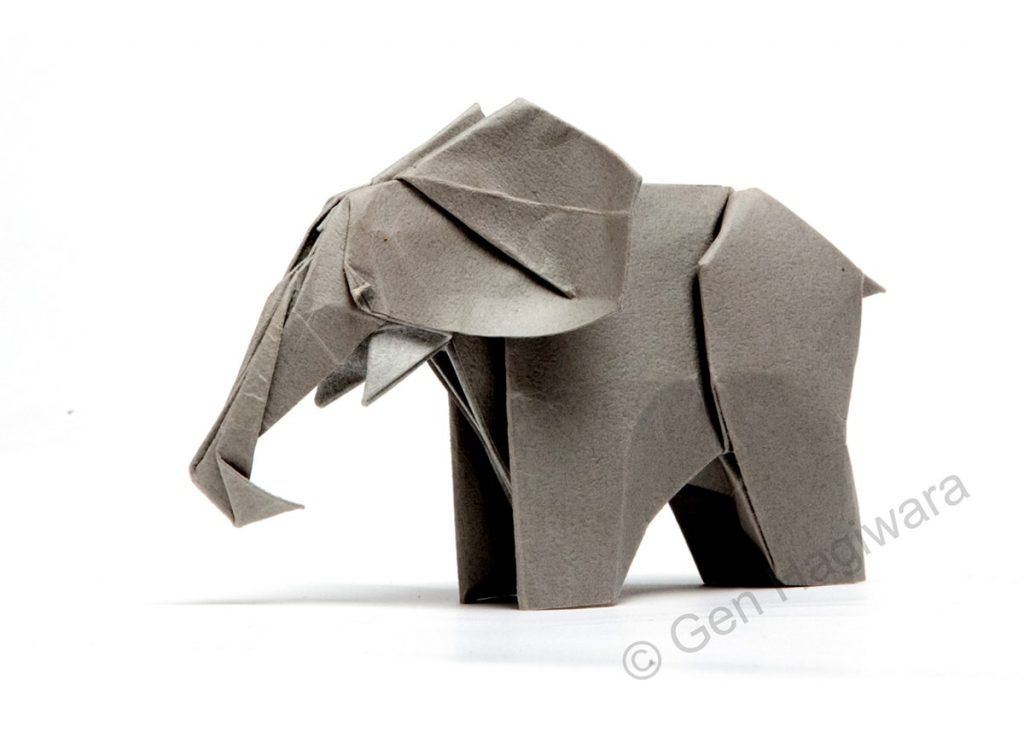

This is where Cohen and his lab come in. Their idea was to use standard fabrication tools used by the semiconductor industry to build the chips, and then build the robot around the chip by folding the robot into the 3D shape they desired. Think origami, but at the microscopic scale.

Like any good origami artist, the researchers at the Cohen lab recognized that it all starts with the paper. Using the unique tools at the Cornell Nanoscale Facility, the Cohen team created the world’s thinnest paper, including one made out of a single sheet of graphene. To clarify, that’s a single atom thickness.

Next, it came to the folding. As Cohen describes, there’s really two main options. The first is to shrink down the origami artist to the microscopic level. He concedes that science doesn’t know how to do that quite yet. Alas, the second strategy is to have the paper fold itself. (I will admit that as an uneducated listener, option number two sounds about as absurd as the first one.) Regardless, this turns out to be the more reasonable option.

The basic process works like this: a seven nanometer thick platinum layer is coated on one side with an inert material. When put in a solution and voltage applied, ions that are dissociated in the solvent will absorb onto the platinum surface. When this happens, a stress is created that bends the device. Reversing the voltage drives away the ions and unbends the device. Applying stiff elements to certain regions restricts the bending to occur only in desired locations. Devices about the thickness of a hair diameter can be created (folded and unfolded) using this method.

As incredible as this is, there is still one defect: it requires a wire to an external power source that attaches onto the device. To solve this problem, the Cohen lab uses photovoltaics (mini solar panels) that attach directly onto the device itself. When light is shined on the photovoltaic (via sunlight or lasers), it moves the limb. With this advance and some continuous tweaking, the Cohen lab was able to develop the world’s smallest walking robot.

The Cohen Lab also achieved “BroBot” – a microrobot that “flexes his muscles” when light is shined on the front photovoltaics and truly “looks like he belongs on a beach somewhere.”

The Cohen Lab successfully eliminated the need for any external wire, but there was still more left to be desired. These robots, including “BroBot” and the Guinness World Record-winning microrobot, still required lasers to activate the limbs. In this sense, as Cohen explains, the robots were “still just marionettes” being controlled by “strings” in the form of laser pulses.

To go beyond this, the Cohen Lab began working with a commercial foundry, X-Fab, to create microchips that would act as a brain that could coordinate the limb movements. In this way, the robots would be able to move on their own, without using lasers pointed at specific photovoltaics. Cohen describes this moment as “cutting the strings on the marionette, and bringing Pinocchio to life.”

This is the final key step in the development of Ant Bot: a microrobot that moves all on its own. It uses a hexapod gate, meaning a tripod on each side. All that has to be done is placing the robot in sunlight, and the brain does the rest of the coordination.

The potential for these kinds of microrobots is nearly limitless. As Cohen emphasizes, the application for robots at the microscale is “basically anything you can imagine doing at the macroscale.” Cleaning surfaces, transporting cargo, building components. Perhaps conducting microsurgeries, or exploring new worlds that appear inaccessible. One particularly promising application is a robot that mimics that movement of cilia – the microscopic cellular hair responsible for countless locomotion and sensory functions in the body. A cilia-covered chip could become the basis of new portable diagnostic devices, enabling field testing that would be much easier, cheaper, and more efficient.

The researchers at the Cohen Lab envision a possible future where microscopic robots are used in swarms to restructure blood vessels, or probe large swathes of the human brain in a new form of healthcare based on quantum materials.

Until now, few would have imagined that the ancient art of origami would predict and enable technology that could transform the future of medicine and accelerate the exploration of the universe.