A Disney star waves their wand, tracing three glowing circles in the air—Mickey Mouse’s head. With that Disney smile, they say, “You’re watching Disney Channel.”

Iconic, right? Instantly recognizable? Absolutely.

Protected? Without a doubt.

Disney holds patents on a variety of innovations—including fireworks that explode into specific shapes. Intellectual property (IP) protections like patents, trademarks and copyrights allow companies to safeguard their creative and technological ideas.

If you think you’ve just come up with the next big breakthrough, the first step isn’t just to celebrate and start working on it—it’s to patent it.

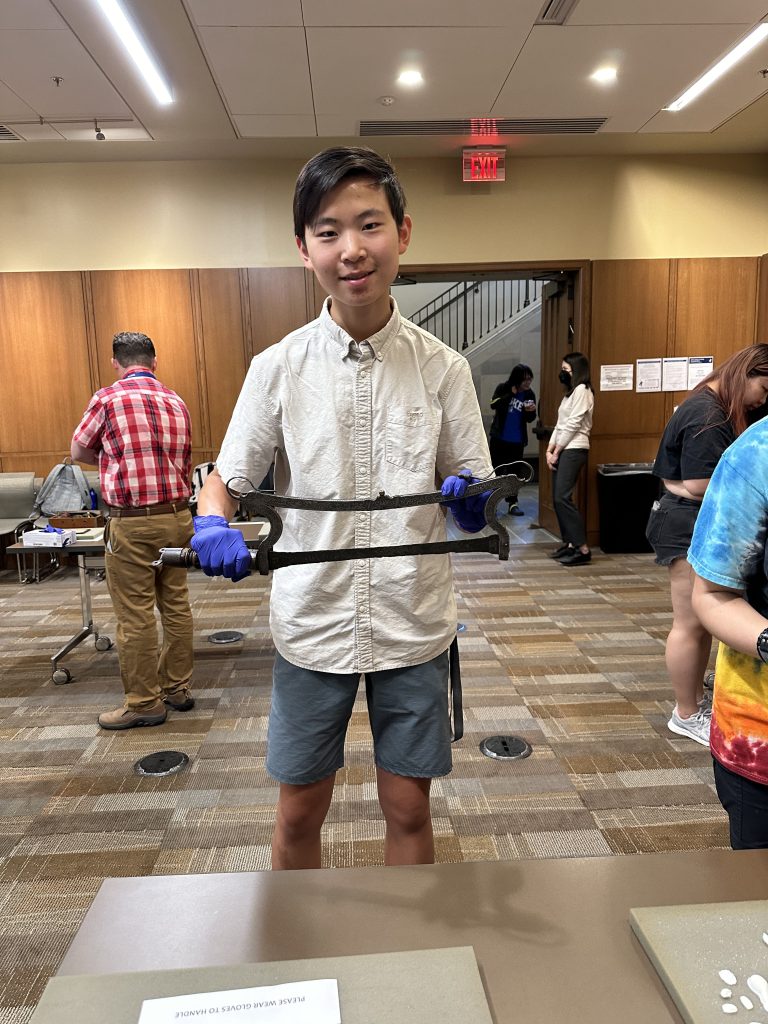

When Jodi Psoter, head of Duke’s Marine Lab Library and an expert in science research strategies, gave a talk on patents, she broke it down for people like me—someone who knew next to nothing about them.

Here’s what I learned:

What Are Patents?

A patent is a legal tool that grants inventors exclusive rights to their inventions for a set period. An important disclaimer, in Psoter’s words, “I wish I had a good meme for the fact that I am not a lawyer – and this is not legal advice.” As a science expert, however, she comprehensively laid out the essentials: what a patent is, how it differs from research articles, when to apply for one, and the steps to do so.

Protecting your work 101 broken down:

- Patents protect inventions, such as a new chemical compound or a technological innovation.

- Trademarks cover branding elements like logos and names (yes, Duke has one!).

- Copyrights safeguard creative works, such as literature, music, and even game designs.

Patents vs Trade Secrets

In addition to patents, another key form of intellectual property protection is trade secrets. Unlike patents, which require public disclosure in exchange for exclusive rights, trade secrets protect valuable, confidential information that gives a company a competitive edge. Jodi Psoter highlighted Coca-Cola’s secret formula as a classic example—closely guarded and never patented to ensure indefinite protection. For something to qualify as a trade secret, three elements must apply:

1. It must have value by the fact that it is not known. If the information were public, it would lose its competitive advantage.

2. Others must want the information. If competitors could benefit from knowing it, it has economic significance.

3. Efforts must be taken to maintain its secrecy. Companies must actively safeguard trade secrets through confidentiality agreements, restricted access, and legal measures.

Unlike patents, which expire after a set period, trade secrets can last indefinitely—as long as they remain secret. If disclosed, whether intentionally or through a breach, they lose protection. This makes them a crucial but high-risk form of intellectual property for businesses aiming to maintain an advantage in their industry.

Similar to patenting, trade secrets are also a crucial step to possibly protect your future work!

Types of Patents

I’m no researcher, quite the opposite in fact. In the simplest terms, for you and me, here are the types of patents:

1. Utility Patents: They cover new processes, machines, or compositions of matter (this is what Disney has for their fireworks!).

2. Design Patents: They protect the visual appearance of a product (Nike, for example, has patented sneaker designs rather than the sneakers themselves).

3. Plant Patents: they apply to new plant varieties produced through asexual reproduction.

Patents must be novel and non-obvious. Psoter explained, “It has to be a new idea. It has to be non-obvious—‘not something where everyone just says, oh well, of course that can happen.’”

When Should You Protect Your Work?

As early as possible!

Psoter emphasized the importance of timing when it comes to patents: “If you show it to the public, that becomes public information, and then you won’t qualify for a patent in the U.S.” In other words, once an invention is fully disclosed—whether in a research paper, presentation, or casual conversation—it may no longer be patentable.

However, researchers often face a dilemma: How much can you publish while still securing a patent? The answer isn’t straightforward, and legal guidance is key. Psoter noted that lawyers can advise on striking the right balance—ensuring that enough information is shared for academic progress without compromising the ability to protect an invention.

If something can’t be patented, there may be alternative protections, such as trade secrets or copyrights. But for patentable innovations, securing rights early is critical to preventing others from capitalizing on your work.

Is Your Idea Already Patented? Find Out Early

Psoter recounted a personal experience: while making long drives to pick up her stepson, she brainstormed an app for finding clean bathrooms along the way—only to discover it already existed. This process, often called a prior art search, involves looking at existing patents to see if someone else has already claimed a similar innovation. The idea is to make sure your concept hasn’t already been patented or publicly disclosed, which would make it ineligible for protection.

“You have to check if your idea has already been patented,” she said, recommending Google Patents and databases like Derwent. She compared patent language to drug names: “Koosh ball? That’s ‘floppy filaments.’ If you look at a drug patent, it’ll be 21 letters long, but in the end, it turns out to be Tylenol.”

But looking for patents may not be that easy.

When searching for patents, using classification codes can be far more effective than relying on keywords alone. Every patent is assigned a specific classification number that categorizes it based on its function and design, helping researchers find related patents and track prior innovations. Jodi Psoter highlighted this through the example of the Beerbrella, a patented umbrella attachment for a beer bottle, classified under A45B11/00—which covers “umbrellas characterized by their shape or attachment.” Additional codes, like A47G23/00 for “other table equipment” and A45B17/00 for “tiltable umbrellas,” further refine the search. Using these classification numbers in Google Patents or Derwent allows researchers to uncover prior patents, identify competitors, and ensure their idea is truly novel before filing a patent application.

Final Thoughts: Why Protecting Your Work Matters

Whether it’s Disney securing its fireworks, Nike patenting sneaker designs, or researchers at Duke innovating in their fields, intellectual property protection is what turns ideas into assets.

Understanding patents, trade secrets, and copyrights isn’t just for corporations—it’s for anyone looking to protect their work, claim credit, and ensure that their innovations make an impact.

As Psoter emphasized, the key is acting early. If you have an idea that could change the world, don’t let it slip into the public domain before securing your rights.

So, next time inspiration strikes, celebrate the idea—but protect it first.

Think you may have an invention?

The Office for Translation and Commercialization helps Duke inventors with IP, startups, and more.

You can also check out Google Patents to explore existing patents.

Or visit the patent resources from Duke Libraries for additional guidance.