Amid fracturing arctic ice shelves, late September tempests, floods, droughts, jumping wildfires, a few decades of quick extinction and species blinking out like the quiet collapse of distant supernovae, our climate crisis has begun to displace humans en masse.

68.5 million people were forcibly displaced by climate change and disasters in 2017. By 2021, that number grew to 89.3 million people. In 2022, we reached 100 million.

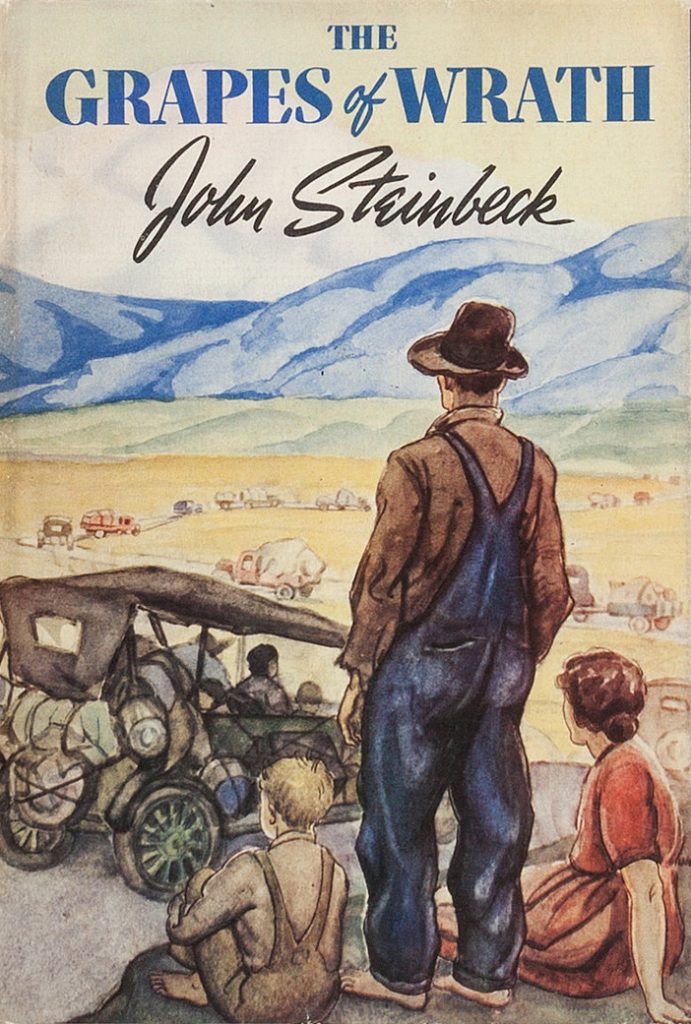

In a series of articles for the San Francisco News entitled “The Harvest Gypsies,” John Steinbeck described the 1930s Dust Bowl migrants in California’s Central Valley, uprooted by drought and crumbling wheat, then later novelized in the American classic Grapes of Wrath.

Steinbeck wrote, “The new migrants from the dust bowl are here to stay. They are the best American stock, intelligent, resourceful; and, if given a chance, socially responsible. To attempt to force them into a peonage of starvation and intimidated despair will be unsuccessful. They can be citizens of the highest type, or they can be an army driven by suffering to take what they need. On their future treatment will depend the course they will be forced to take.”

Alluding to Steinbeck, Dr. Robert McLeman joined Duke’s Dr. Sarah Bermeo for Climate Change, Adaptation and Migration, a conversation on climate-migration and rural impact central to Dr. Kerilyn Schewel’s Rural Development and the Capability to Stay project.

Co-sponsored by Duke Center for International Development (DCID) and the Center on Modernity in Transition (COMIT), the lecture is part of the larger Rural Transformations speaker series, highlighting rural perspectives in the discourse around development. This objective embodies COMIT’s research as well as their cognizance of “modernity as an age of transition towards a future world society—one that will emerge not through the universalization of any existing way of life, but rather through the sustained, creative, and complexly interacting contributions of all the diverse cultures and peoples of the world.”

The Dust Bowl, McLeman pointed out, is a quintessential example of climate migration, conjuring Dorothea Lange’s depression-era photojournalism and 8th grade US history. More recently, this phenomenon has been exemplified by hurricanes Katrina, Ike, Harvey, Irma, Sandy, Ida, Hugo, Andrew, Ian, and Maria (just to name a few) with similar, though smaller scale effects.

As McLeman and Bermeo acknowledged, climate-catalyzed movement is highly dependent on complex interactions between environment, society, economy, and politics, including a myriad of non-ecological factors like “land tenure, social networks, [and] access to government programs.”

Their research on the demographic composition and rates of climate-migration answers a number of questions: who is disproportionately affected by climate change? Who is migrating? And who is participating in policy decisions?

December 2022, the Biden Administration announced a $135 million investment for relocation and adaptation planning for Native American tribes severely impacted by environmental crises, such as “coastal and riverine erosion, permafrost degradation, wildfire, flooding, food insecurity, sea level rise, hurricane impacts, potential levee failure and drought.”

In less than a lifetime, one such tribe, the Jean Charles Choctaw Nation in Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana, witnessed nearly their entire island sink into swampy silt.

On their tribal website, they write: “For our Island people, [Isle de Jean Charles] is more than simply a place to live. It is the epicenter of our Tribe and traditions. It is where our ancestors survived after being displaced by Indian Removal Act-era policies and where we cultivated what has become a unique part of Louisiana culture.

Today, the land that has sustained us for generations is vanishing before our eyes.”

To date, 98% of the island has sunk. The tribe has begun relocation to the New Isle 40 miles north.

Climate migration in America, however, is not contained within and between states. In the past decade alone, Bermeo’s research points to a significant increase in migration from Central America to the US as well as novel patterns of family unit migration to the southern border (as opposed to a predominantly individual, male demographic in previous years). She attributes two recent droughts to this out-migration, disproportionately displacing rural communities whose livelihoods are integrally tied to subsistence farming and year-to-year crop yield.

“People leave their homes because of climate but leave their countries for other reasons,” Bermeo explained. A large percentage of climate-migration is “inter-state,” i.e. a rural coastal community is forced to move inland (but still within their country) because of dangerous erosion.

In Central America, however, there is a distinct relationship between the incidence of drought and violence. Environmental stress has catalyzed a mass exodus from rural areas, increasing urbanization, yet these cities (particularly those in Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador) often rank globally among the most violent, based on year-to-year per capita homicide rates.

With high levels of urban corruption and gang affiliation, it is often difficult for rural “outsiders” to find employment in the cities, leaving them unable to compensate economically for a season of crop failure. This conflict is further exacerbated by large proportions of young workers in these populations.

Despite deep-seated political polarization, climate-migration is adaptive.

McLeman described migration generally as “neither good nor bad… something that people sometimes do and always have done… [But] in North America, we lose sight of the fact that it is normal human behavior… it’s the circumstances under which it occurs that creates the challenges.”

When migration is voluntary, when people have access to social safety nets, are able to remit money to their families back home, and to mobilize legally across borders, migration is beneficial for the migrant, the migrant’s family, and the receiving community (which often benefits by filling labor demands). Often, the ramifications of immigration portrayed in the media (crime, destitution, etc.) are exacerbated by the lack of legality, social networks, and “gray markets.”

Bermeo acknowledged that the most effective mechanisms of decreasing undocumented migration are those that increase legal pathways. Historically, when the US has increased the number of visas allocated to Central American immigrants, illegal immigration subsequently decreased.

The panelists agreed: in order for both the migrating and receiving communities to benefit, we must prioritize the dignity of migrating individuals.

Though conversations surrounding climate change feel threateningly existential, Bermeo and McLeman described ways in which climate adaptation can be manageable. When migrants and rural communities are excluded from conversations and subsequent policy-making, not only do they benefit less from the proposed and funded interventions, but other communities (perhaps at less imminent risk from climate change) will still suffer from this missing insight.

Here, I return to the Jean Charles Choctaw Nation. Despite the appearance of a successful relocation project, the tribal council released a press statement in 2022, condemning the state of Louisiana. Elder Chief Albert Naquin spoke on the issue:

“If you believe that the resettlement of Isle de Jean Charles was successful, you’re headed in the wrong direction.” The memo added that, “Moving people while trampling upon our Tribe’s inherent sovereignty and rights to self-determination and cultural survival must not be viewed as a ‘success’ for future public climate adaptation investments.”

The mass movement of climate-migrants, from Indigenous to rural communities, represents a loss of autonomy, of land integral to identity, and often of home.

Still, Schewel’s Rural Transformation project advocates for the prioritization of these communities, rejecting the notion of passive policy-making and, instead, endorsing their active participation. Her project is indicative of how we must approach climate change adaptation: with empathy, education, and inclusion.

In a conversation with DCID, Schewel put it best: “[R]ural places are often treated as an afterthought… Some of the most promising advances in sustainable and equitable development are taking place in rural contexts, where a diversity of actors are striving to transform food systems, incorporate local knowledge, strengthen climate resilience, and widen participation in the development process.”

The DCID article ends with key insights from Schewel that encompass the Climate Change, Adaptation and Migration discussion and bear repetition: “As more focus is going towards migration, this is a project that will take very seriously the constraints on rural livelihoods and the motivations of migrants who leave rural places, while offering forward-looking solutions to advance our understanding of what it would mean to build more sustainable and flourishing rural futures.”

Next up in the Rural Transformation lecture series: Religion and Development (June 20) and Local Knowledge, Global Change (June 30)