Blake Fauskee, third-year Biology PhD student, initially pitched his graduate project to advisor Kathleen Pryer (Ph.D.) as an undergrad.

Fauskee, who researches RNA editing sites in ferns, told me about the project that he’s been working on for the last several years. His research could push back against the idea that DNA is the end-all, be-all molecule for encoding life as we know it.

Fauskee broke down RNA editing for me. “RNA editing is this extra step in the whole central dogma, the whole gene expression process, that happens in plant organellar DNA,” he said. This process takes place in plant mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes.

Fauskee uses a lot of metaphors to describe his work, which I find both helpful and admirable. Science can often be dense and lack feasible connections to processes that most of us are familiar with. “Basically, in [plant] DNA, there are little typos almost. The wrong nucleotide is encoded at certain spots. When those genes are going to be expressed, they get turned into RNA and then other proteins from the nucleus come in and find the little typos so that in the end you get the correct protein.”

Fauskee calls RNA editing an “interesting and strange process” that neither animals nor humans have. His work attempts to study the evolution of this process, the patterns of RNA editing, and why it came to be. He uses DNA and RNA sequence data and the help of computational tools to do his work. He explains that when sequencing DNA, you can think of the fragmented base pairs “as little puzzle pieces.”

“So, I take all those little puzzle pieces and try to put back together the chloroplast genome, which is about 150,000 base pairs. It’s like a thousand-piece puzzle.”

Next, he figures out where the fern’s gene sequences are on the DNA strands, making use of genomic databases that contain known genomes. He then aligns RNA sequences to the genes he has mapped. Fauskee looks for the “typos” or “little differences” between the DNA and RNA: “That’s how we find the RNA editing sites.” Finally, he evaluates how the proteins would be changed by the typos in the DNA if the RNA was not edited after being transcribed.

“So, a lot of these fern genes will have a STOP codon right in the middle, which is really, really bad if you don’t fix because you are only going to get half a protein,” Fauskee said. STOP codons signal to the protein-building ribosomes that the protein is finished once it reads this portion of the RNA. Fauskee explained that these types of errors are the ones would expect organisms to lose, but it turns out they are the ones that are conserved in ferns. “Is there an extra function there? Is it helpful? Is it adaptive?” Fauskee asked.

Comparative analyses between fern species are important. By looking at whether there are common editing sites and common amino acid changes, Fauskee says, “we’re trying to understand if certain editing sites may be advantageous and what kinds of fluctuation we see between certain types of changes.”

Fauskee underscored the importance of his work. “RNA editing is a really interesting process that kind of undermines what I learned in molecular biology…They always tell you DNA is the bedrock, it’s the be-all, end-all. But what happens when the DNA is wrong? What’s the other added layer on this?”

Simply put, Fauskee, says that because of RNA editing, “We have to rethink central dogma a little bit.” In some plants, 10% of all their gene products contribute to RNA editing, Fauskee tells me. “That’s a big chunk and that’s got to be important,” Fauskee said, “Why would evolution keep such a burden going?”

There may also be implications for how RNA editing sites affect the way that genetic relationships are mapped through phylogenetics. If differences between the DNA of different species at RNA editing sites, this could be misleading. Though the DNA indicates a change in base pair, RNA editing could lead to the same output in protein despite the seeming change. “If you took [RNA editing] into account,” Fauskee says, “does it give you a different answer?”

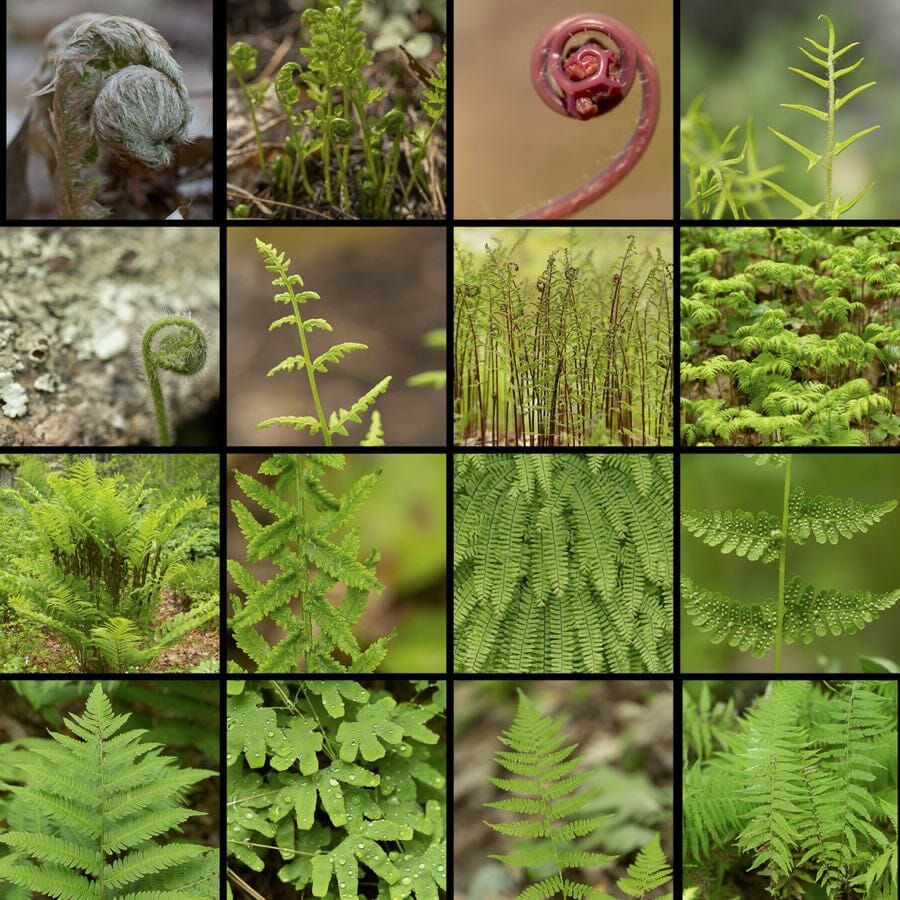

Fauskee studies ferns because of the amount of editing sites found in these plants. While flowering plants have lost editing sites over time, ferns have not. “For RNA editing, you can look at all angiosperms (flowering plants) and for the whole chloroplast genome, they might have 30-50 RNA editing sites. When you get into ferns, that number jumps up to 300-500 and I am trying to understand why.”

Botanical science first captured Fauskee’s interest while he completed his undergraduate degree in his home state at the University of Minnesota Duluth (UMD). As a sophomore at UMD, Fauskee was taken under the wing of Amanda Grusz (Ph.D.). Grusz received her PhD in biology from Duke and worked under Pryer during her own time at the university. “I’m like my advisor’s academic grandson, which is kind of funny.” Clara Howell, who is part of Fauskee’s PhD cohort and who I spoke with last Fall, is also an academic grandchild in her own lab.

Being an “academic grandson” has worked out well for Fauskee. His key advice to me for any person considering a PhD, “Make sure your advisor is not someone you just admire as a scientist, but as a person.” On a day-to-day basis, Fauskee says that advisor Katheen Pryer “is pretty hands off” but is also “one of the most supportive people ever. I’m pretty much the driver of my own ship. If I am falling off the road, she’ll push me back on the road, but she’ll give me freedom to swerve around on that road.”

Fauskee also emphasized a piece of wisdom that Pryer passed down to him. “If whatever you’ve got going on is working and everyone else is doing something different, who cares?” he said.

Though Fauskee says that “lab work can be frustrating,” getting his long analyses to run after wrangling lots of data is very rewarding. Fauskee, who does not have a background in coding or computer languages, likes to “tell people that [his] floor of biology combined is one competent coder.” When he’s not stealing bits of his biology neighbor’s code, Fauskee loves to attend Duke Basketball games and is a fan of the television show Survivor.

Post by Cydney Livingston, Class of 2022