Covid-19 is considered a “general pandemic,” but its impacts have been disproportionate along the lines of race and ethnicity. Though vaccines may serve as our best chance to put an end to Covid, the problem of vaccine hesitancy amongst Black people in the U.S. is particularly pervasive and grounded by more than simple mistrust.

Gary Bennett (Ph.D.) discussed the issue of complex determinants of vaccine hesitancy among Black Americans Monday, April 5. Bennett is a Professor of Psychology, Neuroscience, Global Health, and Medicine at Duke, as well as director of Duke Digital Health and Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education.

“At the end of the day, we are dealing with an issue that demands pragmatic attention,” Bennett said, “How do we get shots in arms?” It turns out, the answer is quite complex and historically confounded.

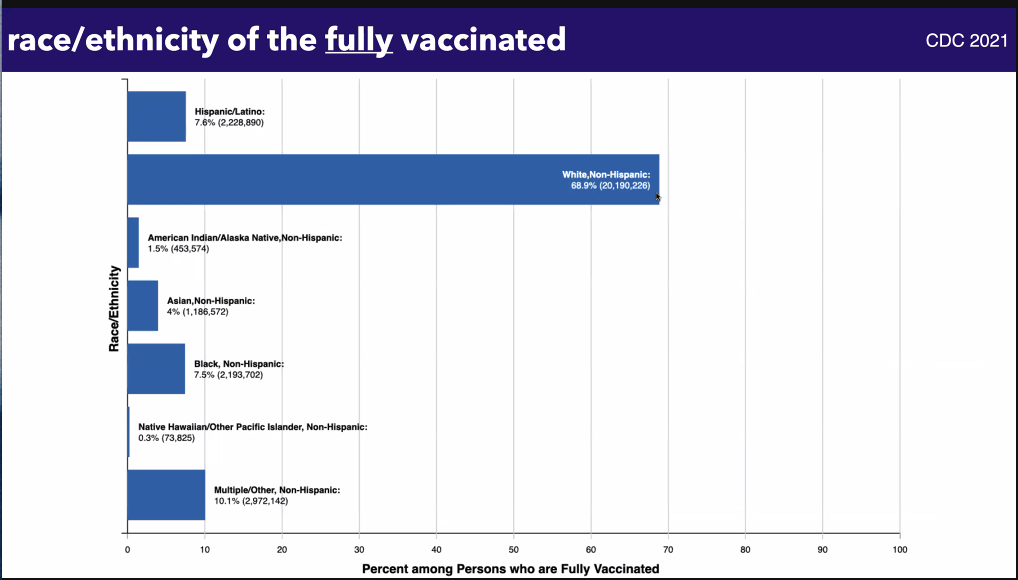

While Black people have experienced much higher burdens from Covid-19 despite contracting the disease at a similar rate to whites, they have been disproportionately vaccinated at lower rates than white people.

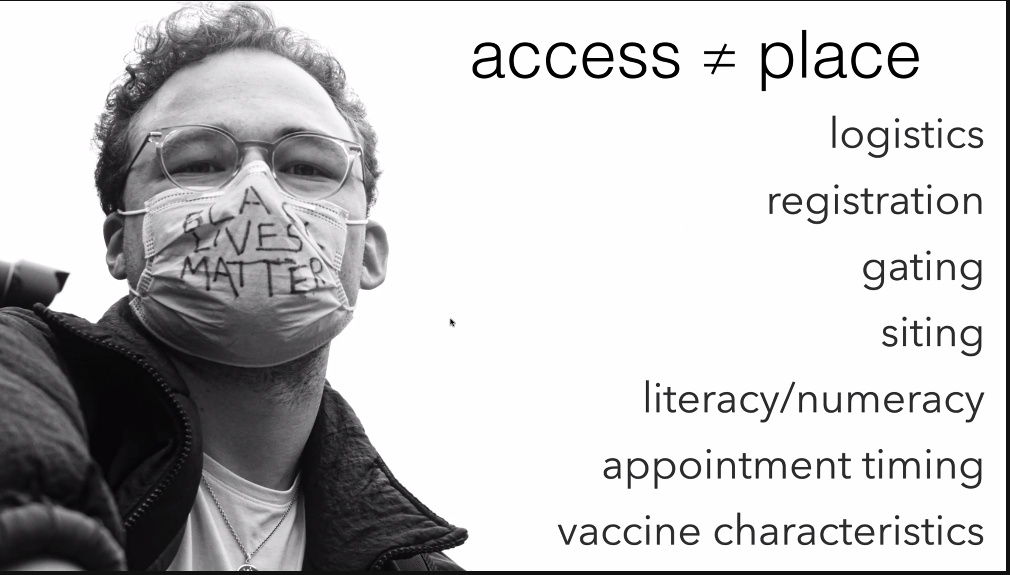

“Access matters and it matters a lot,” Bennett said. One clear example of decreased access for Black Americans is that fewer vaccination sites are located in areas with high concentrations of Black people.

However, Bennett said, access does not simply equal place. “How much friction are you creating in this process?” he prompted, pointing to examples of complicated registration systems, inadequate public transportation to vaccine sites, or overall distance from a location. All of these factors already limit who is able to access vaccinations without the added influences of reduced vaccine uptake due to vaccine hesitancy.

Vaccine hesitancy was listed by the World Health Organization as a top 10 global threat in 2019, when vaccines were preventing 2-3 million deaths per year in the pre-Covid era. Though Bennett said that vaccine hesitancy “has been with us for a long time,” there “are real consequences” to continued reluctance and refusal to get vaccinated with heightened risks due to the nature of the pandemic.

Bennett said that many claims around hesitancy blame communities for their inability to access vaccines, but this fails to consider or to change the underlying behaviors that drive hesitancy. Bennett outlined these underlying drivers as 1) mistrust, 2) social norms, and 3) understandable uncertainties.

“It’s not just mistrust of the medical system, it’s mistrust of institutions,” Bennett said, “There’s a lot of reasons for [Black people] to mistrust institutions.” The murder of George Floyd stands as one poignant contemporary example, but “Tuskegee [still] looms large in the minds of Black Americans.” The Tuskegee experiment exploited 600 Black men working as sharecroppers who had syphilis by knowingly withholding treatment and simply seeing what happened to their bodies as a result of the disease for over 40 years.

This experiment was not the first of its kind: Whole body radiation was tested on Black people. Fistula surgery was developed on enslaved Black women by the “father of modern gynecology.” The immortal cells of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman, have been used far and wide to advance science after a sample of her cancerous cervix was unknowingly stolen from her. Modern studies have also shown how different implicit biases of Black patients shape their treatment outcomes due to skewed physician perceptions.

Our social networks are also vitally important to influencing our feelings about receiving the Covid vaccine. In Black communities, Bennett said, fewer people in their networks have gotten vaccinations and those who have received vaccines are less vocal about it leading to a collective lack of interest in receiving vaccinations.

These two factors, paired with understandable uncertainties about the side effects of the vaccine or potentially getting Covid itself, generate the need to change our approaches to vaccine hesitancy and increased uptake amongst Black communities in the U.S.

To do this we need to lead with empathy and appreciate the fact that changing attitudes towards vaccines is a process. “Shaming people is bad,” Bennett said. “Stigmatizing people will actually lead to the converse of what we expect.”

Over time, we can work to correct misconceptions, contextualized uncertainties, and share stories rather than statistics to push people further from vaccine refusal and closer to vaccine demand.

And when more Black Americans are ready, “vaccination should be an easy choice.” By implementing opt-out policies, rather than opt-in and by taking more direct actions like making vaccination appointments for people, Covid vaccines may indeed be the key to ending the pandemic – in an equitable and proportionate way.

Post by Cydney Livingston