We are still in the midst of an opioid epidemic. In 2019, an average of six North Carolinians died each day from unintentional medication or drug overdose. A striking 79% of drug overdose deaths in NC in 2018 involved opioids. This has garnered attention from many organizations and institutions in the state and prompted new concerns relating to patient-centered care.

A Duke Global Health discussion on March 17 concluded that the social response can be aided by a refined focus on mental health, as well as the use of telehealth – the delivery of health care and education remotely through various technologies.

Moderated by Brandon Knettel (Ph.D.), the Duke Global Health Institute panel considered treatment, community engagement, and public policy in addressing the opioid epidemic with panelists Nidhi Sachdeva (MPH), Padma Gulur (M.D.) Hilary Campbell (PharmD, J.D.), and Theresa Coles (Ph.D.)

Sachdeva is a Senior Research Program Leader with the Department of Population Health Sciences at Duke Medical School. Dr. Gulur is a Professor of Anesthesiology and Population Health with Duke Medical School and Executive Vice Chair of the Pain Management and Opioid Surveillance with Duke University Health System. Campbell is director of Sheps Health Workforce Health Professions Data System at UNC-Chapel Hill. Coles is Assistant Professor in Population Health Sciences with Duke Medical School.

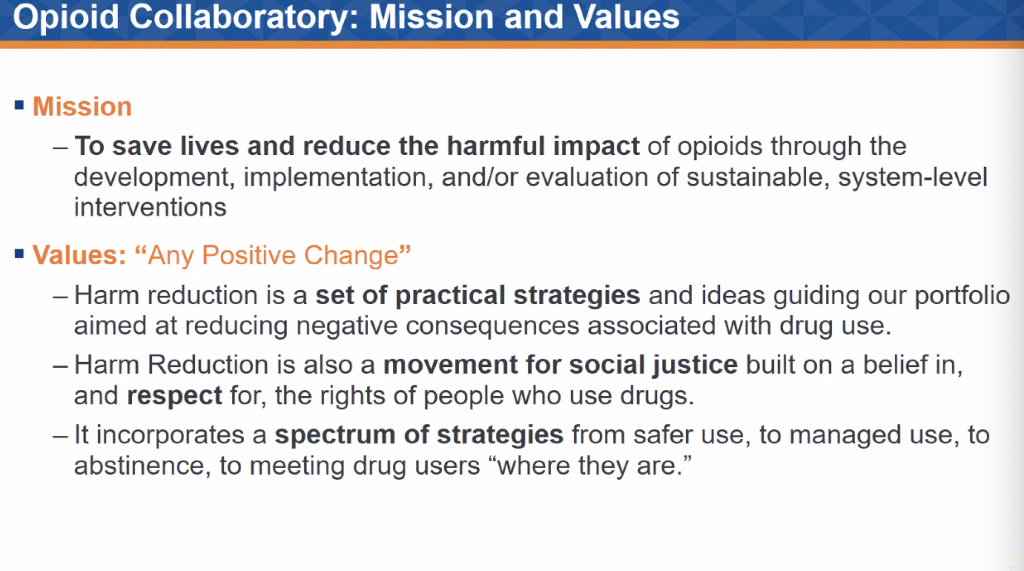

Sachdeva opened the panel with a discussion of the Duke Opioid Collaboratory. The Collaboratory currently houses 25 different projects relating to improving data surveillance, health system quality, and public health in the realm of research on opioids.

“We’re losing more and more folks every day,” said Sachdeva. Duke’s projects represent a systems approach to the opioid epidemic, meaning there is lots of valuable overlap and connectivity between projects, and external partnerships that have provided a unique opportunity for academic and community collaboration.

Dr. Gulur stated that Duke Health has seen improvements in opioid use and prescription over the last five to six years: the ambulatory prescribing rate has gone down, fewer patients are requiring high-dose opioids overall, and there has been significant increase in availability to offer medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder. Like Sachdeva, Gulur’s work with Duke’s Pain Management and Opioid Surveillance exists within a larger network of organizations dedicated to the opioid issue.

“We have a very committed and collaborative infrastructure with [other] initiatives in the state,” said Gulur, who added that she is dedicated to making “sure we have all the voices at the table.”

Simply decreasing opioid prescriptions “doesn’t necessarily work” and solving this issue will not be a quick fix. Campbell said that her own research found that at the same time the “supply side” of opioids was shrinking, the state was “seeing the crisis getting worse.”

Enter telehealth and the need for expanded support to mental health resources. Coles explained their pertinence through discussion of her work with Granville-Vance Public Health. Coles has been working on an expanding project that assesses training, operational challenges, patient centered goals, and success from the patient’s perspective within Granville-Vance’s opioid program.

Coles found that inconsistent funding lead to lapses in access to mental health support and the “dropout of someone there to help [with behavioral health] was challenging for patients.” Telehealth bridges the gaps of inconsistent access. Further, in the case of Coles’ study, it also played a large role in increased access for patients who experienced transportation issues since the investigation took place in conjunction to Covid-19, which lowered patients’ abilities to physically attend the program in-person.

Because “no one person experiences opioid abuse … in a vacuum,” as Sachdeva said, it is important to get a comprehensive “assessment of what a person’s life looks like and their priorities for treatment” before jumping into treatment.

Though the last year living under the Covid-19 pandemic has been difficult for the entire globe, the increased need for access to resources through the internet and various technologies has been positively reinforced. With new understandings of relationships to others and limited physical access to in-person healthcare, telehealth has emerged as a means to resolve decreased access. It can also serve as a way to expand access for populations who have historically suffered from inadequate access to healthcare resources, like rural populations.

Opioids “have and will continue to play a role in pain management,” Dr. Gulur said. However, better efforts to involve patients and their families in decision making around opioids, as well as more fully informed understandings of the potential risks and side effects, is necessary for centering patient priorities in care management.

Sachdeva emphasized a “nothing about us without us” philosophy for approaching the opioid epidemic. This means that the systems of care being changed to address opioid crises must depend directly on people who use opioids. It is important to center “lived experience through the whole thing.” Because each community is different, it is inadequate to make assumptions about “what a community is, what it might need, or what its story is.”

Underlying this work is a question from Dr. Gulur, “What are you trying to treat?”

To treat the opioid epidemic, we need to treat people as complex, multi-dimensional people living complicated lives. Opioid use is only one facet of this narrative, making it pertinent to understand the rest of the story to adequately tackle this problem our nation faces. Mental health and access to care are central to this collective narrative more largely.

Post by Cydney Livingston