University of North Carolina cell biologist Efra Rivera-Serrano says he doesn’t look like a stereotypical scientist: he’s gay, Puerto Rican, and a personal trainer.

Known on Twitter as @NakedCapsid or “the guy who looks totally buff & posts microscopy threads,” he tweets about virology and cell biology and aims to make science more accessible to the non-science public.

But science communication encompasses more than posting the facts of viral transmission or sending virtual valentines featuring virus-infected cells, Rivera-Serrano says. As a science communicator, he’s also committed to conveying truths that are even more rarely expressed in the science world today. He’s committed to diversity.

Rivera-Serrano’s path through academia has been far from linear — largely because of the microaggressions (which are sometimes not so micro) that he’s faced within educational institutions. He’s been approached while shopping by a construction work recruiter and told by a graduate adviser in biology to “stop talking like a Puerto Rican.”

He’s a scientist at UNC—and also a personal trainer.

Photo from @NakedCapsid Twitter

And the worst part is that he’s far from being the only one in this kind of position. That’s why Rivera-Serrano holds one simple question close to heart:

What would a cell do?

“I use this question to shape the way I tackle problems,” Rivera-Serrano says. After all, a key component of virology is the importance of intercellular communication in controlling disease spread. Similarly, a major goal of diversity-related science communication is “priming” others to fight stereotypes and biases about who belongs in science.

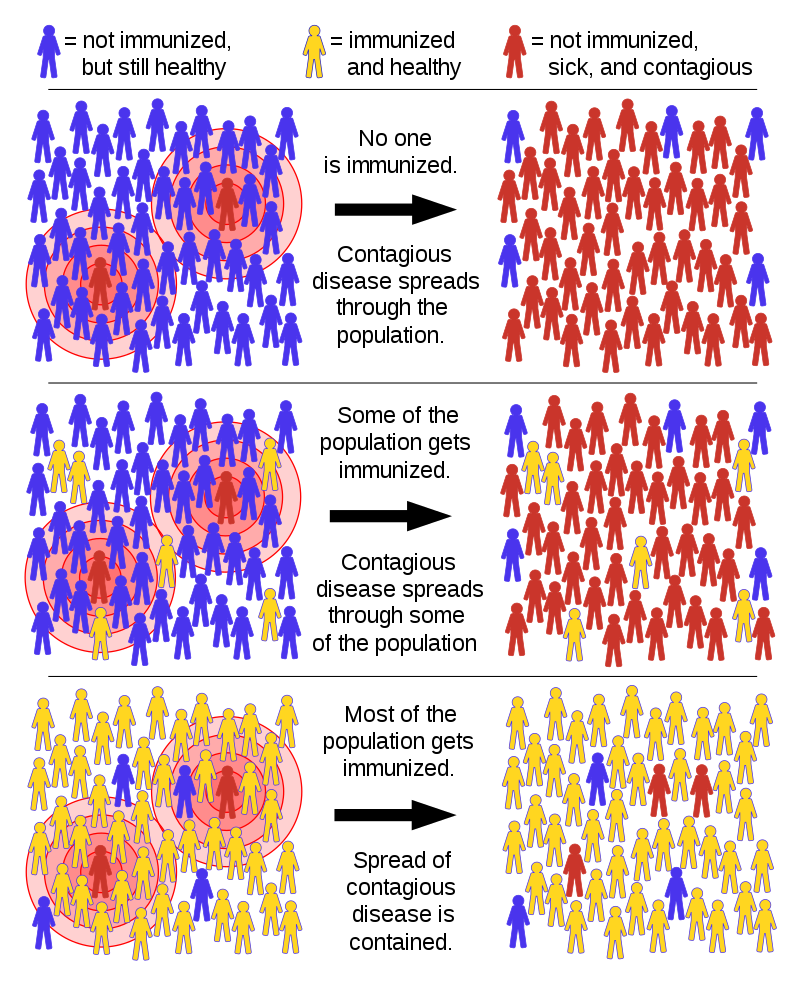

Virology’s “herd immunity” theory operates under the principle that higher vaccination rates mean fewer infections. For some viruses, a 90% vaccination rate is all it takes to completely eradicate an infection from existing in a population. Rivera-Serrano, therefore, hopes to use inclusive science communication as a vaccination tool of sorts to combat discriminatory practices and ideologies in science. He isn’t looking for 100% of the world to agree with him—only enough to make it work.

Image by Tkarcher via Wikimedia Commons

This desire for “inclusive science communication” led Rivera-Serrano to found Unique Scientists, a website that showcases and celebrates diverse scientists from across the globe. Scientists from underrepresented backgrounds can submit a biography and photo to the site and have them published for the world’s aspiring scientists to see.

Generating social herd immunity needs to start from an early age, and Unique Scientists has proven itself useful for this purpose. Before introducing the website, school teachers asked their students to draw a scientist. “It’s usually a man who’s white with crazy hair,” according to Rivera-Serrano. Then, they were given the same instructions after browsing through the site, and the results were remarkable.

“Having kids understand pronouns or see an African American in ecology—that’s all something you can do,” Rivera-Serrano explains. It doesn’t take an insane amount of effort to tackle this virus.

What it does take, though, is cooperation. “It’s not a one-person job, for sure,” Rivera-Serrano says. But maybe we can get there together.