Like many students, those enrolled in the Design Climate two-course sequence recently held final presentations. However, their pitches on April 18 reflected not just one semester of work, but rather an entire year’s worth of planning, experimenting, and revising creative environmental solutions.

These courses are a tinkering space, so it shouldn’t have surprised me how much some of the projects had transformed in concept since they were pitched at the Energy Week Innovation Showcase in November. The team Connexus, which recently become incorporated, aims to bring more people into solar installation and weatherization jobs via an unlikely tool: virtual reality.

An earlier version of this project focused more narrowly on bringing jobs and energy security to Enfield, North Carolina via microloans and financial literacy. In this rural town, many live below the poverty line and suffer from high energy rates. When the team began exploring the concept of building solar infrastructure in Enfield, they found this had been tried before to little avail.

So instead, they focused on how to bridge people to the jobs needed in the field.

Duke students Samson Bienstock, Karimah Preston, and Tyler Rahe–all graduate students with engineering backgrounds–emphasized that with the increased number of people entering college, there’s a growing gap to be filled in the trades.

“There’s students who are looking to get into jobs that don’t require college, and there’s also companies that are looking to hire them, but they’re not exactly sure where they meet in the middle,” said Preston. Connexus essentially plans to be middle man, accelerating job placement by training graduating high school students.

They differentiate themselves from other recruiting companies with VR. Through virtual training modules, high schoolers that might otherwise not consider these careers can experience what it might be like to work as a solar installer or in another trade. This training is “gamified to help engage them and…interact with what they’d be doing on the real job site,” said Rahe. “We would then assess them and screen them based on their job readiness, to see where they would be a great fit and place them directly into these companies…”

Beyond prompting interest, the benefit of using VR is that potential employees can receive training before ever stepping foot on the actual job. Connexus believes that because of this, businesses that utilize their services would likely see better retention rates in workers.

At the UNC Cleantech Summit, Rahe said they surveyed people on “how compelling and clear our ideas are and what what the need actually is…We were testing that assumption. Is this need actually there, or are these just stats [sic]?” According to him, they received promising results: “high recommendations from investors, from educational institutes, [and] from companies that require skilled trades.”

So while Connexus were originally inspired by Enfield, their solution isn’t specialized to only serve one community. They plan to offer services throughout the Carolinas, partnering with colleges and high schools. “Environmentally, we’re hoping to fuel great infrastructure development and support the energy transition,” Preston said.

Meanwhile, Andrew Johnson, Eesha Yaqub, Adiya Jumagaliyeva, Claire Qiu, Mark Lamendola, and Joey Offen are working with chemistry professor Jie Liu on reducing the environmental impact of creating fertilizer. The last time I spoke to Lamendola, a graduate student at the Nicholas School of the Environment, his team was looking to upscale a carbon neutral method for producing synthetic methane. Since then, the group has slightly pivoted, becoming LightSyn Labs.

“In the first semester we looked at the sort of the carbon dioxide to methane pathway, and we still think that’s a viable commercialization opportunity,” Lamendola said. However, the group decided to make the change after speaking to the Luol Deng Foundation. Founded by its Duke basketball alum namesake, it’s based in South Sudan, a largely rural country that relies on agriculture.

That’s important, because their new focus is on using a less carbon intensive process to create ammonia, the main ingredient in most fertilizers. Currently, almost all ammonia production occurs through the Haber-Bosch process, in which hydrogen and nitrogen react to form ammonia. While its discovery greatly improved agricultural returns, the Haber process also requires a lot of energy.

LightSyn Labs is looking to replace it with a method called plasmonic catalysis, developed at Duke by Jie Liu and his colleagues. “It’s activated by light,” Lamendola said. Unlike the Haber process, “it doesn’t rely on high pressure and temperature to drive the reaction.” That means less energy is required and as a result, lower greenhouse emissions and lower costs for farmers, all without disrupting food security. As a “system that requires no heavy infrastructure,” this type of green ammonia production can also occur locally instead of relying on global supply chains, increasing self-sufficiency among South Sudanese farmers.

In a way, everything leading up to this presentation is a warm up for a much larger pitch. This team has been chosen to compete for cash prizes in the EnergyTech Up University Prize Challenge, hosted by the US Department of Energy’s Office of Technology Transitions. Looking even further than that, they predict they’ll need four years–and some strategic partnerships–for LightSyn Labs to fully launch.

The spirit of the Design Climate program is one rooted in entrepreneurship and real-world feasibility. This far from the end for these teams–in fact, this stage is just the beginning.

By Crystal Han, Class of 2028

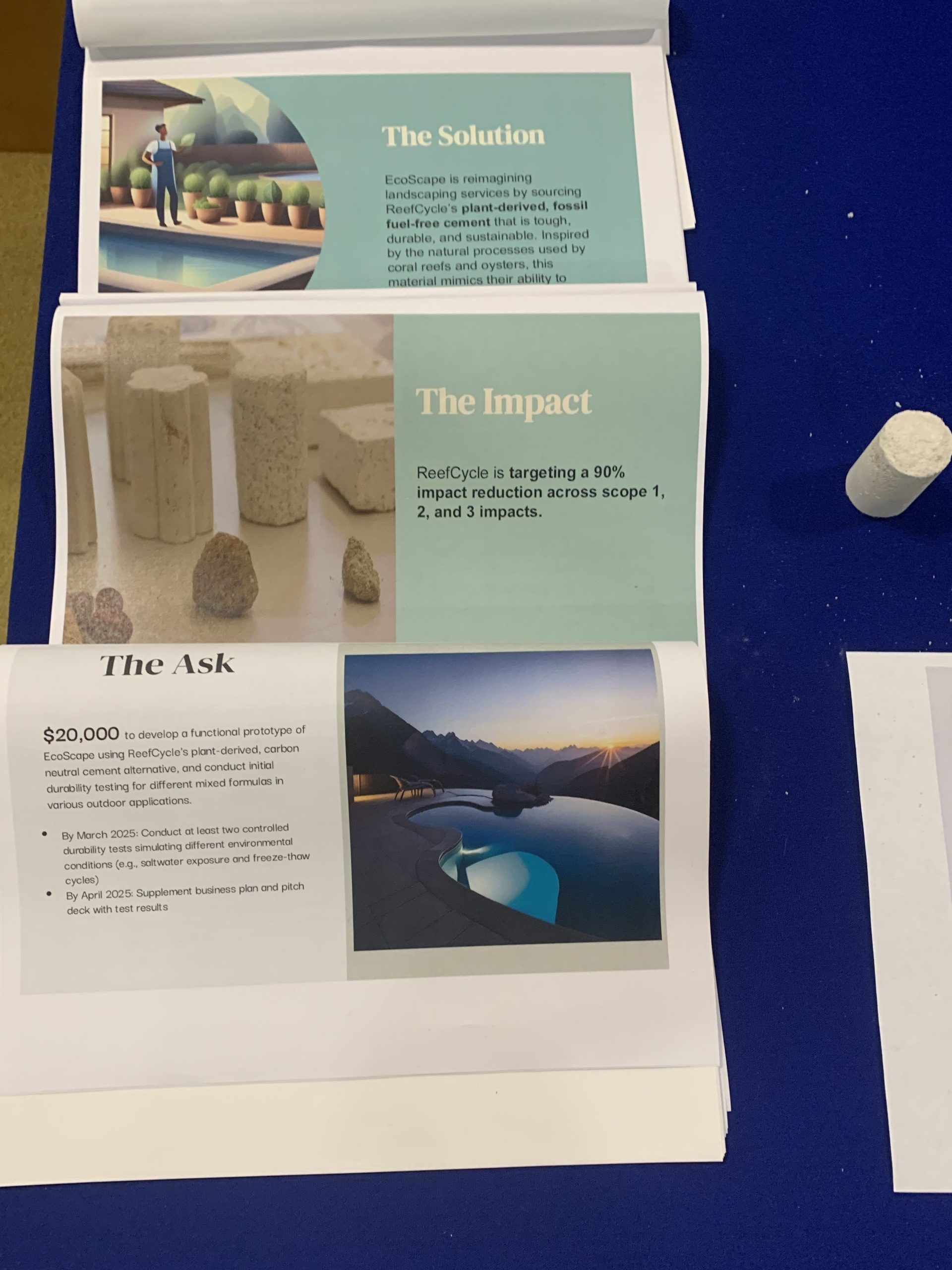

based and enzymatic, meaning it’s essentially grown using enzymes from beans. Testing in the New York Harbor yielded some promise: the cement appeared to resist corrosion, while becoming home for some oysters. The Design Climate team is now trying to bring it to more widespread use on land, while targeting up to a 90% reduction in carbon emissions

based and enzymatic, meaning it’s essentially grown using enzymes from beans. Testing in the New York Harbor yielded some promise: the cement appeared to resist corrosion, while becoming home for some oysters. The Design Climate team is now trying to bring it to more widespread use on land, while targeting up to a 90% reduction in carbon emissions