The COVID-19 epidemic has impacted the Duke research enterprise in profound ways. Nearly all laboratory-based research has been temporarily halted, except for research directly connected to the fight against COVID-19. It will take much time to return to normal, and that process of renewal will be gradual and will be implemented carefully.

Trying to put this situation into a broader perspective, I thought of the 1939 essay by Abraham Flexner published in Harper’s magazine, entitled “The Usefulness of Useless Knowledge.” Flexner was the founding Director of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, and in that essay, he ruminated on much of the type of knowledge acquired at research universities — knowledge motivated by no objective other than the basic human desire to understand. As Flexner said, the pursuit of this type of knowledge sometimes leads to surprises that transform the way we see that which was previously taken for granted, or for which we had previously given up hope. Such knowledge is sometimes very useful, in highly unintended ways.

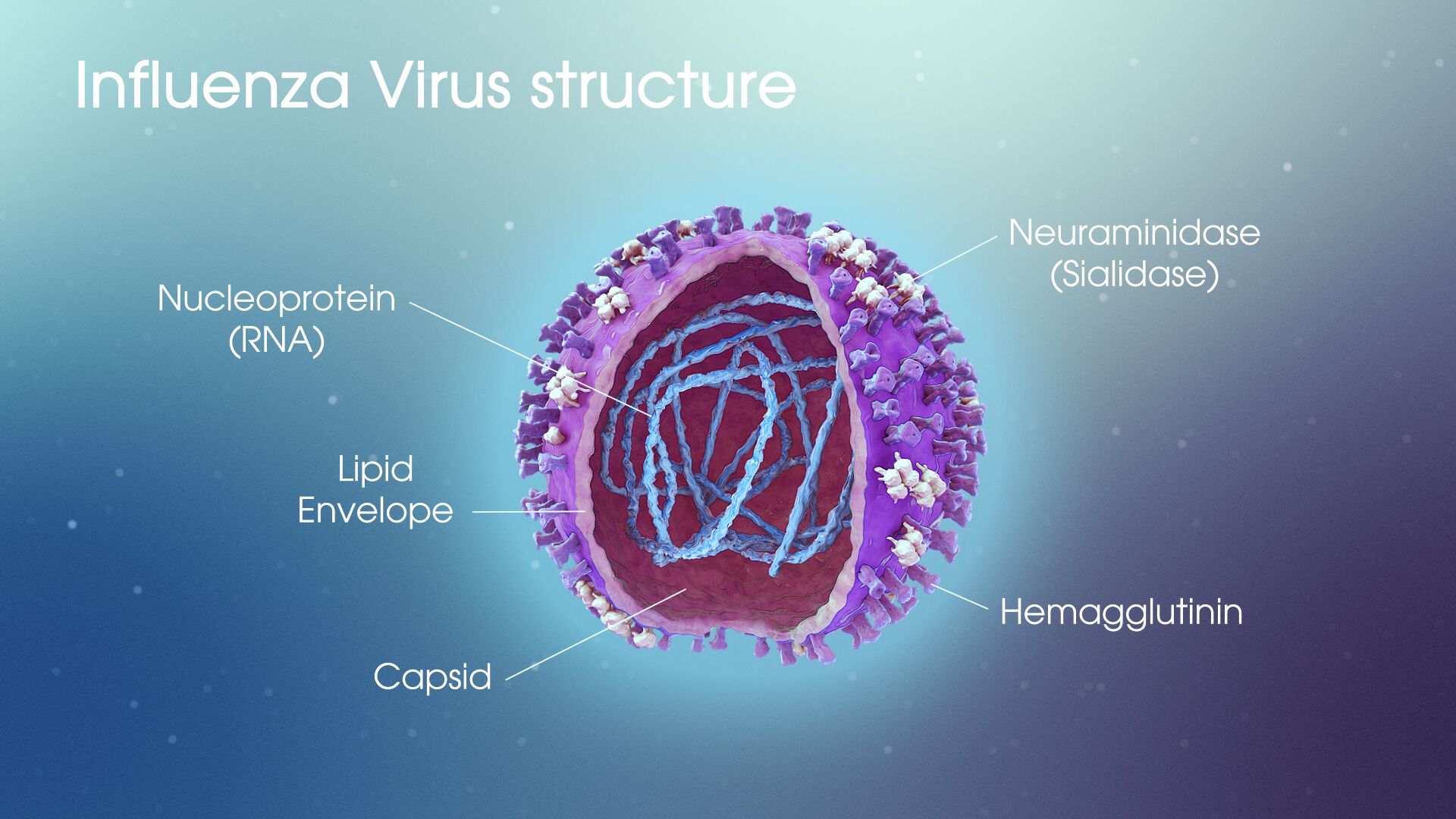

The 1918 influenza pandemic led to 500 million confirmed cases, and 50 million deaths. In the Century since, consider how far we have come in our understanding of epidemics, and how that knowledge has impacted our ability to respond. People like Greg Gray, a professor of medicine and member of the Duke Global Health Institute (DGHI), have been quietly studying viruses for many years, including how viruses at domestic animal farms and food markets can leap from animals to humans. Many believe the COVID-19 virus started from a bat and was transferred to a human. Dr. Gray has been a global leader in studying this mechanism of a potential viral pandemic, doing much of his work in Asia, and that experience makes him uniquely positioned to provide understanding of our current predicament.

From the health-policy perspective, Mark McClellan, Director of the Duke Margolis Center for Health Policy, has been a leading voice in understanding viruses and the best policy responses to an epidemic. As a former FDA director, he has experience bringing policy to life, and his voice carries weight in the halls of Washington. Drawing on faculty from across Duke and its extensive applied policy research capacity, the Margolis Center has been at the forefront in guiding policymakers in responding to COVID-19.

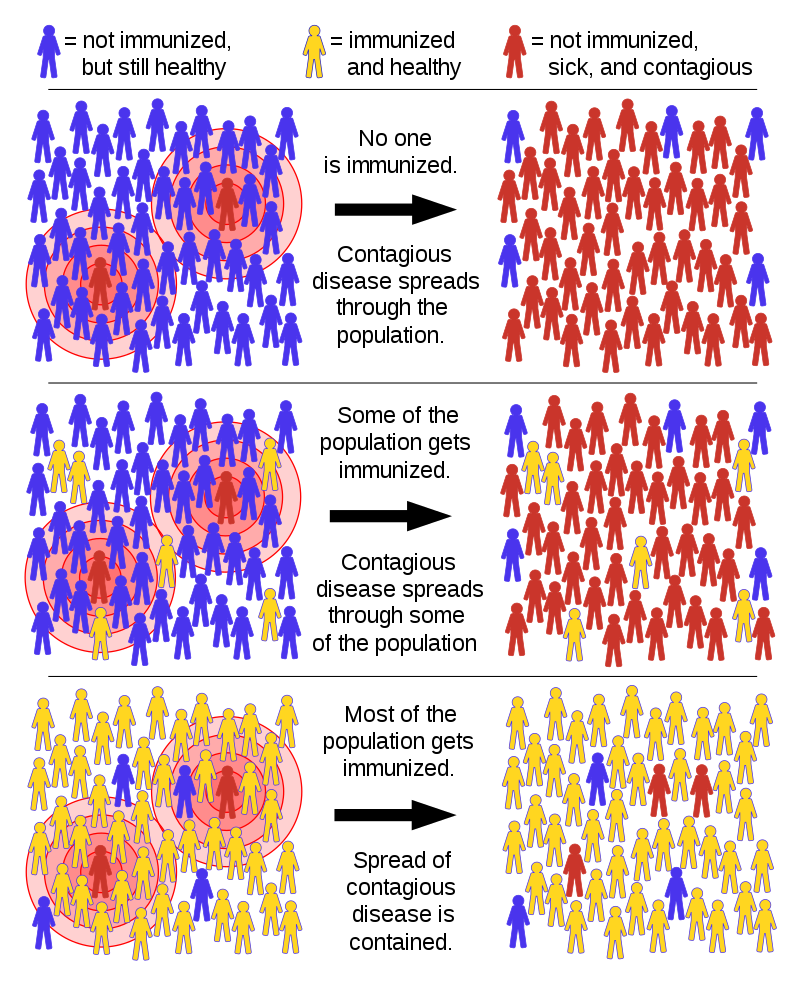

Through knowledge accrued by academic leaders like Drs. Gray and McClellan, one notes with awe the difference in how the world has responded to a viral threat today, relative to 100 years ago. While there has been significant turmoil in many people’s lives today, as well as significant hardship, the number of global deaths caused by COVID-19 has been reduced substantially relative to 1918.

One of the seemingly unusual aspects of COVID-19 is that a substantial fraction of the population infected by the virus has no symptoms. However, those asymptomatic individuals shed the virus and infect others. While most people have no or mild symptoms, other people have very adverse effects to COVID-19, some dying quickly.

This heterogeneous response to COVID-19 is a characteristic of viruses studied by Chris Woods, a professor medicine in infectious diseases. Dr. Woods, and his colleagues in the Schools of Medicine and Engineering, have investigated this phenomenon for years, long before the current crisis, focusing their studies on the genomic response of the human host to a virus. This knowledge of viruses has made Dr. Woods and his colleagues leading voices in understanding COVID-19, and guiding the clinical response.

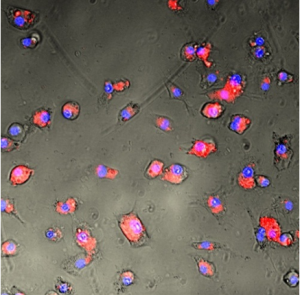

A team led by Greg Sempowski, a professor of pathology in the Human Vaccine Institute is working to isolate protective antibodies from SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals to see if they may be used as drugs to prevent or treat COVID-19. They’re seeking antibodies that can neutralize or kill the virus, which are called neutralizing antibodies.

Many believe that only a vaccine for COVID-19 can truly return life to normal. Human Vaccine Institute Director Barton Haynes, and his colleagues are at the forefront of developing that vaccine to provide human resistance to COVID-19. Dr. Haynes has been focusing on vaccine research for numerous years, and now that work is at the forefront in the fight against COVID-19.

Engineering and materials science have also advanced significantly since 1918. Ken Gall, a professor of mechanical engineering and materials science has led Duke’s novel application of 3D printing to develop methods for creatively designing personal protective equipment (PPE). These PPE are being used in the Duke hospital, and throughout the world to protect healthcare providers in the fight against COVID-19.

Much of the work discussed above, in addition to being motivated by the desire to understand and adapt to viruses, is motivated from the perspective that viruses must be fought to extend human life.

In contrast, several years ago Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, academics at Berkeley and the Max Planck Institute, respectively, asked a seemingly useless question. They wanted to understand how bacteria defended themselves against a virus. What may have made this work seem even more useless is that the specific class of viruses (called phage) that infect bacteria do not cause human disease. Useless stuff! The kind of work that can only take place at a university. That basic research led to the discovery of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR), a bacterial defense system against viruses, as a tool for manipulating genome sequences. Unexpectedly, CRISPR manifested an almost unbelievable ability to edit the genome, with the potential to cure previously incurable genetic diseases.

Charles Gersbach, a professor of Biomedical Engineering, and his colleagues at Duke are at the forefront of CRISPR research for gene and cell therapy. In fact, he is working with Duke surgery professor and gene therapy expert Aravind Asokan to engineer another class of viruses, recently approved by the FDA for other gene therapies, to deliver CRISPR to diseased tissues. Far from a killer, the modified virus is essential to getting CRISPR to the right tissues to perform gene editing in a manner that was previously thought impossible. There is hope that CRISPR technology can lead to cures for sickle cell and other genetic blood disorders. It is also being used to fight cancer and muscular dystrophy, among many other diseases and it is being used at Duke by Dr. Gersbach in the fight against COVID-19.

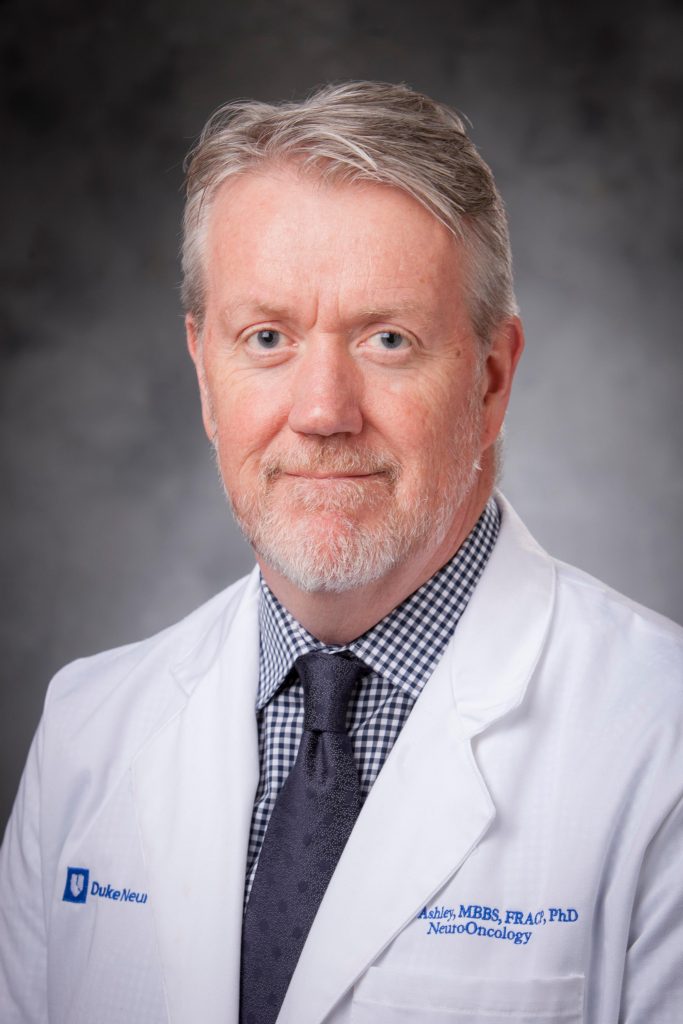

In another seemingly bizarre use of a virus, a modified form of the polio virus is being used at Duke to fight glioblastoma, a brain tumor. That work is being pursued within the Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center, for which David Ashley is the Director. The use of modified polio virus excites the innate human immune system to fight glioblastoma, and extends life in ways that were previously unimaginable. But there are still many basic-science questions that must be overcome. The remarkable extension of life with polio-based immunotherapy occurs for only 20% of glioblastoma patients. Why? Recall from the work of Dr. Woods discussed above, and from our own observation of COVID-19, not all people respond to viruses in the same way. Could this explain the mixed effectiveness of immunotherapy for glioblastoma? It is not known at this time, although Dr. Ashley feels it is likely to be a key factor. Much research is required, to better understand the diversity in the host response to viruses, and to further improve immunotherapy.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a challenge that is disrupting all aspects of life. Through fundamental research being done at Duke, our understanding of such a pandemic has advanced markedly, speeding and improving our capacity to respond. By innovative partnerships between Duke engineers and clinicians, novel methods are being developed to protect frontline medical professionals. Further, via innovative technologies like CRISPR and immunotherapy — that could only seem like science fiction in 1918 (and as recently as 2010!) — viruses are being used to save lives for previously intractable diseases.

Viruses can be killers, but they are also scientific marvels. This is the promise of fundamental research; this is the impact of Duke research.

“We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.”

T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets

Post by Lawrence Carin, Vice President for Research

Post by Anne Littlewood

Post by Anne Littlewood

Post by Lydia Goff

Post by Lydia Goff