I have a nemesis (a bird that defies my searching). Actually, I have several, but I have been preoccupied with this particular nemesis for months.

I have seen an evening grosbeak exactly once, in a zoo, which emphatically does not count. For years, I have been fixated on-and-off (mostly on) with the possibility of seeing one in the wild.

“Evening Grosbeak” by sedge23 is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

They have thick, conical beaks. The males are sunset-colored. (But good luck finding one at sunset, even though the first recorded sighting supposedly happened at twilight, hence their name.) I daydream about flocks of them descending on my bird feeders at home or wandering onto Duke’s campus. That hasn’t happened yet (unless it has happened while I have not been watching, an excruciating possibility I will simply have to live with).

Evening grosbeaks usually live in Canada and the northern U.S., but they are known to irrupt into areas farther south. Irruptions often occur in response to lower supplies of seeds and cones in a bird’s typical range, making it possible to predict bird irruptions, at least if you’re the famous finch forecaster. (Fun fact: “irrupt” literally means “break into,” whereas “erupt” means “break out.”)

Breaking news: The grosbeaks are in Durham, and they have been since December. I will wait while you perform any necessary reactions, including screaming, jumping up and down in delight, charging outside because you simply have to go find them right now, or telling me I must be mistaken.

I am not mistaken. There is a flock of evening grosbeaks overwintering at Flat River Impoundment, 11.8 miles from Duke University. I know this because I get hourly rare bird alerts by email, and I have been receiving emails about evening grosbeaks nearly every day for almost three months. Put another way, evening grosbeaks have been actively and no doubt intentionally taunting me for weeks on end.

Wild Ones, a student organization I’m involved with, had been thinking of organizing a birding trip. For reasons I will not even attempt to deny, I suggested Flat River Waterfowl Impoundment. Last Sunday, seven undergraduates drove there, armed with field guides and binoculars and visions of evening grosbeaks bursting into sight (okay, maybe that was just me).

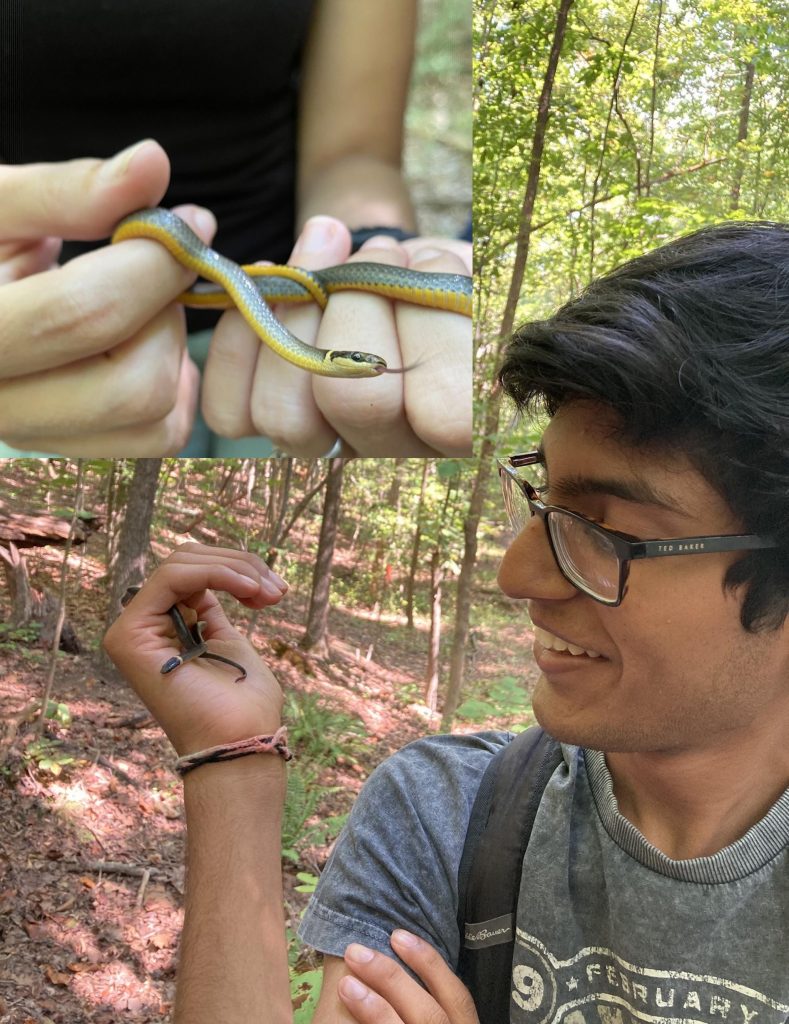

Photo by Adam Kosinski.

The morning was chilly but sunny. Flat River is a gorgeous, swampy place full of small ponds and stretches of long grass edged with trees. As soon as we got there, we were serenaded with birdsong: the high, musical trill of pine warblers, the haunting coo of mourning doves, lilting Carolina wren songs, and squeaky-dog-toy brown-headed nuthatch calls.

It wasn’t long before people got to experience the frustrating side of birding. We were admiring a sparrow in a ditch, trying to guess its identity. Someone pulled out a field guide and flipped through the sparrow section only to turn back to the bird and find it gone. Birds can fly. But fortunately, we’d collectively noticed enough field marks to feel reasonably confident identifying it as a swamp sparrow.

Photo by Lydia Cox, Wild Ones member. (We are not related, if you’re wondering.)

We found two other sparrow species later: song sparrows and white-throated sparrows. Sparrows tend to be small, brownish, and streaky, but certain features can help distinguish some of the common species around here. I’m personally not very familiar with the swamp sparrow, but it has a rusty cap and gray face. The song sparrow has brown stripes on its head, extensive streaking on its underside, and a dark spot on its breast. The white-throated sparrow has striking black-and-white stripes on the top of its head, yellow lores on its face (the spot in front of the eye), and yes, a white throat. (Just don’t rely too much on bird names for identification. Red-bellied woodpeckers definitely have red heads but usually only have red bellies if you’re rather imaginative, but beware—they’re still red-bellied, not red-headed woodpeckers. Meanwhile, there are dozens of warblers with yellow on them, but only one of them is a yellow warbler. Nashville warblers only pass through Nashville during migration, and American robins aren’t robins at all.)

Photo by Lydia Cox.

We saw Carolina chickadees flitting through trees, an Eastern phoebe doing its characteristic tail-wagging, and a Cooper’s hawk feeding on prey. Then, thrillingly, we spotted a bald eagle soaring through the sky. The bald eagle, America’s national bird since 1782, was in danger of extinction for years, largely due to the insecticide DDT, which made their eggs so thin that even being incubated by their parents could make them crack. However, the bald eagle was removed from the endangered species list in 2007, and populations have continued to increase.

Photo by Lydia Cox.

Not long after the eagle sighting, we saw another flying raptor: an osprey. In fact, it must have been a good day for raptors because by the end of our trip we had recorded one osprey, two Cooper’s hawks, three bald eagles, and two red-tailed hawks.

We also saw a lot of birders—perhaps two dozen others, maybe more, not counting our own group. Each time we passed a group going in the opposite direction, I asked them if they’d found the grosbeaks.

Photo taken with my phone through my binoculars, a technique that is slowly teaching me a modicum of patience.

I think everyone I asked had seen them, and they were all eager to point us in the right direction. Birders like to use landmarks like “by the eagles’ nest” and “the fifth pine on the right” and “past the crossbills.” We found the eagles’ nest, with help from some of the local birders. We think we found the fifth pine on the right, but there were a lot of pines there, so we’re not sure.

We did not find the red crossbills, another irruptive bird species overwintering here this year. (Crossbills are aptly named. The tips of their mandibles really do cross, which helps them access seeds inside cones.)

“Red Crossbills (Male)” by Elaine R. Wilson, www.naturespicsonline.com is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

We found the spot where the evening grosbeaks had most recently been seen — just twenty minutes before we got there, according to the people we were talking to. We waited. We scrutinized the pine trees. We watched red-tailed hawks and bald eagles circle high above us. We admired the eagles’ nest, a huge collection of sticks high in a pine tree.

Would you like to guess what we did not find? My nemesis. Because the evening grosbeaks have devious minds and clearly flew all the way to Durham with the sole intent of hiding from me, dodging me, flying away as soon as I approached, and flying back again as soon as I was gone. (No, really. Other people reported them at Flat River that same day, both before and after our trip there.)

Photo by Adam Kosinski.

Birding can be intensely frustrating. It can plant images in your mind that will haunt you and taunt you for the rest of your life. Like, for instance, the tiny blue bird I caught a brief glimpse of in the trees one early morning in Yellowstone. For years, I wondered if it could have been a cerulean warbler, but cerulean warblers don’t live in the western U.S. Or let’s talk about the green bird—yes, I swear it was green; no, I can’t prove it—that came to my bird feeders several years ago and never came back. Not while I was watching, anyway. The only thing I can think of for that one is a female painted bunting, but painted buntings aren’t usually in upstate South Carolina. (If my local volunteer eBird reviewer in South Carolina ever happens to read this, I promise I won’t report either of those mystery sightings to eBird.) Or, of course, the evening grosbeaks that flew away twenty minutes before we arrived.

Birding can also be thrilling, meditative, and by all accounts wonderful. Yes, that little blue bird in Yellowstone and the maybe-green one in my backyard are branded in my memory, as are countless more moments of maybe and almost and what if? I will never know what they were. I will probably never get over it.

But there are other moments that stick in my mind just as clearly. The bald eagle soaring above us on this Wild Ones trip. The black-capped chickadee that landed on my finger years ago while my brother and I rested our hands on a bird feeder and waited to see what would happen. My first glimpse of a black-throated blue warbler (I am so proud of whoever named that bird species), chasing an equally tiny Carolina chickadee in my backyard.

“131. The Black-throated Blue Warbler (Sylvicola canadensis) 132. He Cape-May Warbler (Sylvicola maritima) 133. The Nashville Warbler (Syvicola ruficapilla) illustration from Zoology of New york (1842 – 1844) by James Ellsworth De Kay (1792-1851).” by Free Public Domain Illustrations by rawpixel is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

The Cape May warbler I saw with a close friend in a small field covered in purple wildflowers. The first time I heard the loud, ringing Teacher-teacher-teacher! song of the ovenbird. A blackpoll warbler, the first I’d ever seen, in a grove of trees in a swampy field that only birders seem to find reason to visit.

The moment two Carolina wrens took food from my hand for the first time. Prothonotary warblers (another nemesis bird) practically dripping from the trees on a rainy, buggy hike along a boardwalk. The downy woodpecker that landed on my gloved hand, apparently too impatient to wait for me to finish what I was doing with the suet feeder, and pecked at the suet with that sharp beak, her black tongue flicking in and out, her talons clinging to me with a trust that brought tears to my eyes.

Birding can change you. It can make your world come alive in a whole new way. It can make traveling somewhere new feel all the more magical — a new soundscape, new flashes of colors and patterns, a new set of beings that make a place what it is. In the same way, birding can make home feel all the more like home. Even when I can’t name all the birds that are making noise in my yard, there is a familiarity to their collective symphony, a comforting sense of “You are here.” I encourage you to watch and listen to birds, too, to join the quasi-cult that birding can be, to trek through somewhere wet and dark when the sky is just beginning to lighten—or to simply step outside, wherever you are, and listen and watch and wait right here and right now. You don’t even need to know their names (though once you start, good luck stopping). And you certainly don’t need a nemesis bird. In fact, your birding experience will be calmer without one. But that might not be up to you, in the end. Nemesis birds have minds of their own.

Post by Sophie Cox, Class of 2025