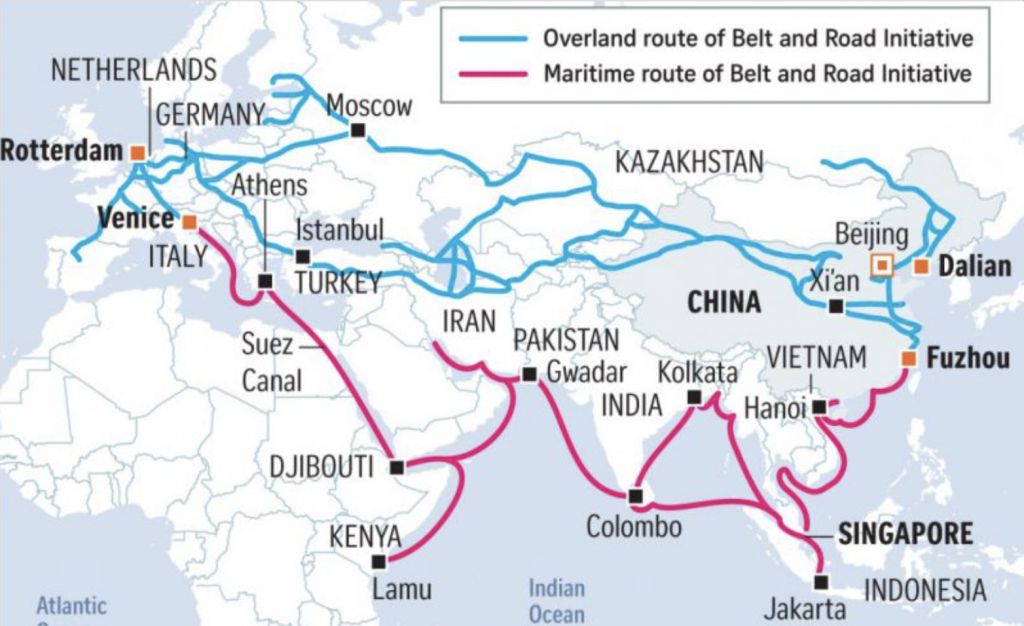

Whether it was Marco Polo traversing the Silk Road (which was more like Silk Routes), Columbus sailing the ocean blue, or even Moana restoring the heart to Te Fiti; oceans have been integral to our way of life as humans for thousands and thousands of years.

But humans have always been bad at sharing – most wars are fought over territory, land especially. And as time has passed, the things we share as humans has evolved – from oceans and land to the Internet and outer space. So how do you keep things diplomatic? Last Friday, Duke’s Space Diplomacy Lab, co-chaired by Dr. Benjamin Schmitt of Harvard University and Duke’s own Dr. Giovanni Zanalda, hosted a webinar on what space diplomacy can learn from ocean diplomacy. Featuring Dr. Clare Fieseler of the Smithsonian Institution and Dr. Alex Kahl of the National Marine Fisheries Service, the conversation covered everything from zoning to equity to even the lessons we can learn from Indigenous communities.

Sharing data and sharing fish

There are multiple challenges to sharing the world’s waterways. Fieseler did not start out her career studying ocean diplomacy. Initially stationed in the Persian Gulf, building a marine mammal monitoring network, she noticed that the fraught state of politic affairs in the region made it hard to share data on the animals that were washing up on the shore.

Meanwhile, Kahl, who works in Hawaii as the National Resources Manager at the National Marine Fisheries Service, runs into problems not in sharing data but primarily in sharing fish. “How do you focus on the shared exploitation of a natural resource?” he asked.

Two key themes arose in linking the sharing of the ocean to the sharing of outer space.

First, Fieseler pointed out that engaging scientists can help in transcending politics, something that ocean diplomacy does well. She pointed to efforts to establish a Marine Peace Park between North Korea and South Korea, and that if two of the worlds most polarized countries could come to an agreement in the name of science and human betterment, then “surely other countries can too.”

Second, Kahl remarked, unlike in the ocean, the primary resource in space is, well, space. You need fish to eat to survive – do you need space to survive?

Centering equity

On the topic of whether we really need space in space to survive, Kahl pointed to the significance that many celestial bodies have in cultures here on Earth, such as in Hawaii and the Pacific Islands. Does interfering with these celestial bodies cross a red line for cultures on Earth? It’s worth noting that as Kahl said, with space exploration, “very few people are profiting,” so balancing the interests of people on Earth as well as in space is important.

Fieseler spoke to the need to build equity in space through some sort of formal agreement, similar to the Law of the Sea. But, she says, that might be skipping a few steps. Right now, “many developing countries can’t even afford to go to space.” How can you build equity in a region where not everyone even has a seat at the table? Kahl pointed out that this marginalization impedes discussions on how to share space – something that should be consensus-driven.

Zoning

As Fiesler remarked, zoning of the ocean has been key to a relatively peaceful sharing of this resource for the variety of uses that people have for the sea. A good example of this is the Antarctic Treaty, which zoned different places in Antarctica for scientific use.

Kahl spoke to being a beneficiary of the Antarctic Treaty – “it reduces bureaucratic burdens, and the collective benefits are also increased.” However, he made the point that the slicing and dicing of space, as with anything, could lead to initial tensions.

Science should have a seat at the table

A central theme that ran throughout the conversation was that, as Kahl put it, scientists “rely on each other to level-set the truth” – even in spaces where they might be in the minority, such as in a room of politicians engaging in diplomatic talks.

Fieseler pointed to how in environmental justice work, her Indigenous colleagues were good at taking the initiative – and finding the urgency – to demand a seat at the table. “As scientists, we sit around, thinking that one day the phone will ring and someone will invite me to be a part of the conversation – but that’s not how it works.” Diplomacy will always be a necessity as we aim to navigate sharing the vast resources at our disposal, but many scientists hope that we won’t forget to center the pursuit of the truth as we make decisions.