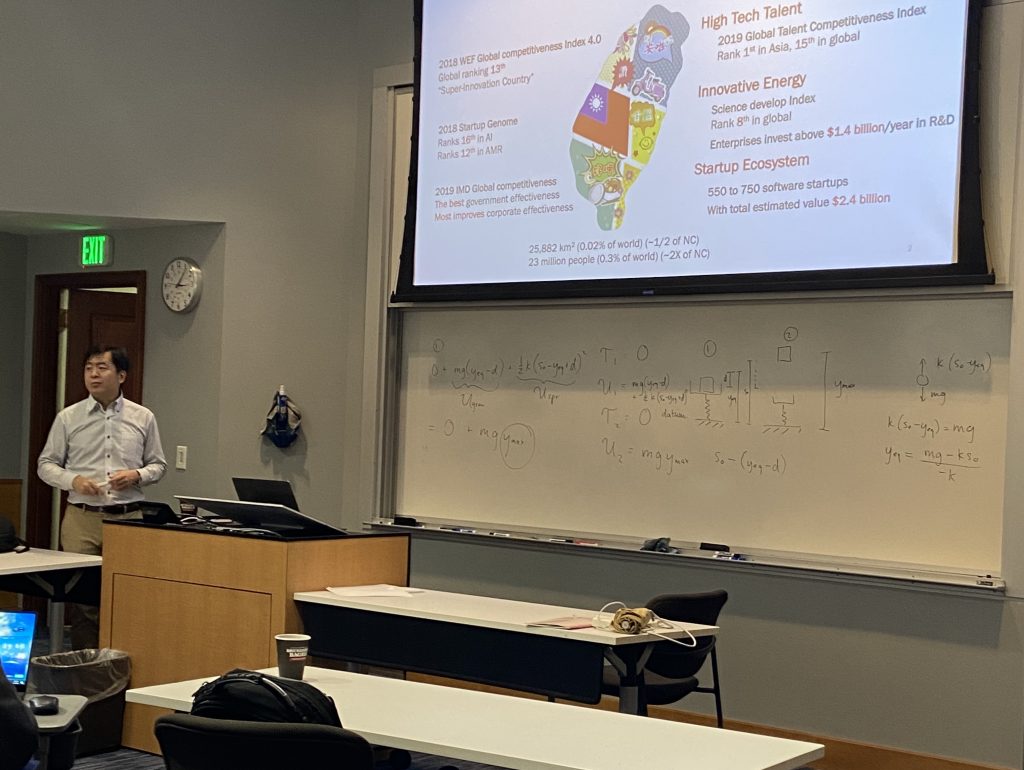

Taiwan is a small island off the coast of China that is roughly one fourth the size of North Carolina. Despite its size, Taiwan has made significant waves in the fields of science and technology. In the 2019 Global Talent Competitiveness Index Taiwan (labeled as Chinese Taipei) ranked number 1 in Asia and 15th globally.

However, despite being ahead of many countries in terms of technological innovation, Taiwan was still looking for further ways to improve and support research within the country. Therefore, in 2017 the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST), initiated an AI innovation research program in order to promote the development of AI technologies and attract top AI professionals to work in Taiwan.

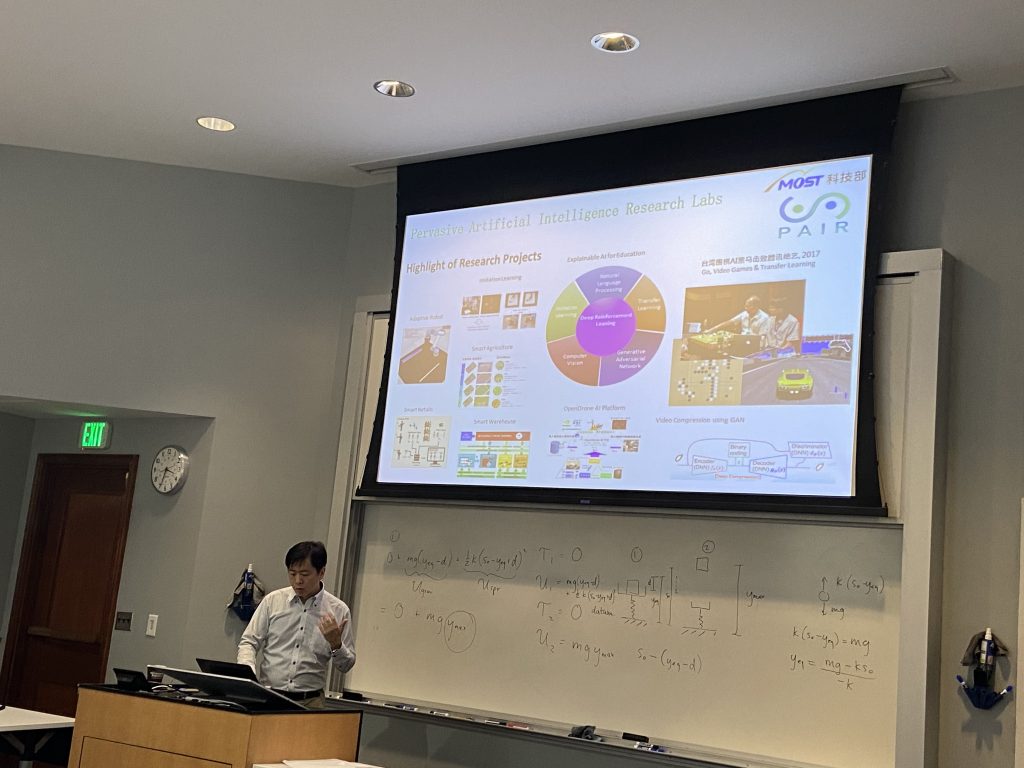

Tsung-Yi Ho, a professor at the Department of Computer Science of National Tsing Hua University in Hsinchu, Taiwan came to Duke to present on the four AI centers that have been launched since then: the MOST Joint Research Center for AI Technology, All Vista Healthcare (AINTU), the AI for Intelligent Manufacturing Systems Research Center (AIMS), the Pervasive AI Research (PAIR) Labs, and the MOST AI Biomedical Research Center (AIBMRC) at National Taiwan University, National Tsing Hua University, National Chiao Tung University, and National Cheng Kung University, respectively.

Within the four research centers, there are 79 research teams with more than 600 professors, experts, and researchers. The centers are focused on smart agriculture, smart factories, AI biomedical research, and AI manufacturing.

The research centers have many different AI-focused programs. Tsung-Yi Ho first discussed the AI cloud service program. In the last two years since the program has been launched, they have created the Taiwania 2 supercomputer that has a computing capacity of 9 quadrillion floating-point operations per second. The supercomputer is ranked 20th in computing power and 10th in energy efficiency.

Next, Tsung-Yi Ho introduced the AI semiconductor Moonshot Program. They have been working on cognitive computing and AI chips, next-generation memory design, IoT System and Security for Intelligent edge, innovative sensing devices, circuits, and systems, emerging semiconductor processes, materials, and device technology, and component circuit and system design for unmanned vehicle system and AR/VR application.

One of the things Taiwan is known for is manufacturing. The research centers are also looking to incorporate AI into manufacturing through motion generation, production line, and process optimization.

Keeping up with the biggest technological trends, the MOST research centers are all doing work to develop human-robot interactions, autonomous drones, and embedded AI on for self-driving cars.

Lastly, some of the research groups are focused on medical technological innovation including the advancement of brain image segmentation, homecare robots, and precision medicine.

Beyond this, the MOST has sponsored several programming, robotic and other contests to support tech growth and young innovators.

Tsung-Yi Ho’s goal in presenting at Duke was to showcase the research highlights among four centers and bring research opportunities to attendees of Duke.

If interested, Duke students can reach out to Dina Khalilova to connect with Tsung-Yi Ho and get involved with the incredible AI innovation in Taiwan.

Post by Anna Gotskind